25. THE ACCIDENTAL IMAGE

In the process of filmmaking, most elements you see on screen have been placed there strategically. In fiction feature filmmaking, for instance, it is the prop(erty) master’s job to provide the director with the required ‘props’ on set: a particular chair or car, for instance, which might help explain some part of a character’s story, or motivation.

In animation, in which the images are literally created from scratch, everything you see on screen has been the result of a deliberate decision. Indeed, in each episode of The Game is On! series, visual ‘clues’, such as the print on a t-shirt, the posters on the wall – or even the wallpaper itself – have been ‘planted’ for you to discover and link to the theme of the episode.

In other kinds of filmmaking, such as documentary filmmaking, the situation is different. In documentaries – roughly defined as films grounded in real life – the story sometimes develops in front of the camera as it is happening. This means that background elements, such as a television programme playing on a screen in a corner of the shot, the music that is playing in a shopping mall, or a ringtone – in other words, other people’s copyright material – may accidentally make it into the film.

Some documentary filmmakers make use of other people’s material in a different way: they back up their arguments with historical images, either moving images or photographs. And there are also filmmakers who see themselves primarily as artists and who only use other people’s material to create new work: a form of filmmaking often called found footage filmmaking.

When can you use someone else’s work in your own work without asking for permission? What are the copyright exceptions that a filmmaker can depend upon? In this Case File #25 we explore the relationship between documentary filmmaking, the re-use of other people’s work and copyright exceptions.

COPYRIGHT EXCEPTIONS: WHAT IS FAIR?

In some of the previous case files we have seen that UK copyright law provides for a number of exceptions to copyright, specific circumstances when work can be used without the need to get permission from the copyright holder (have a look at Case File #5, #6, or #24). There are various copyright exceptions set out in the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (the CDPA), concerning non-commercial research and private study, news reporting, parody, education, and other uses.

A number of these exceptions are sometimes referred to as ‘fair dealing’ exceptions because the law requires that your use of the material for that particular purpose must be fair. Indeed, each copyright exception has specific requirements about how and when the material can be used without permission, and in order to benefit from an exception you must make sure you satisfy the relevant requirements.

Being properly informed as a filmmaker about what is fair dealing will enable you to confidently create your new work, and to avoid rights clearance problems dictating what makes it into your film or not. To know when you are able to quote from other people’s copyright material without having to ask for permission will expand the range of what you can make. Another consequence of relying on fair dealing is that it can save you a lot of money, which is great news for documentary filmmakers who often work with a limited budget.

Let’s consider the specific section of the CDPA that deals with quotations.

Section 30(1ZA) of the CDPA tells us that you can quote from a work if: the work has been made available to the public, the use of the quotation is fair dealing, the extent of the quotation is no more than is required by the specific purpose for which it is used, and the quotation is accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement (unless this is impractical).

The CDPA does not specifically define ‘fair dealing’. Some factors have been identified by the courts as relevant in deciding whether a particular use is fair, but as the UK Intellectual Property Office (IPO) states: it will always be a matter of fact, degree and impression in each case.

One relevant factor to consider is the purpose behind using the work: does the material have a different effect than in its original use? Is there a clear connection between the use of the clip and the intention of the larger film? Does it add context or has it been used for mere creative value? Consider, for instance, feature films that rely on archival footage to add an air of ‘authenticity’ to their dramatic stories, such as Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit (2017), Roman Polanski’s The Pianist (2002), or Oliver Stone’s JFK (1991). The archival clips in those films are used for a creative purpose only, and no new context is given – through the addition of a voice-over, for instance.

If this is the kind of film you intend to make, it may be difficult to argue that your use of the work is fair dealing. You should probably get permission from the rights holders instead. However, if you used the same clip of the Warsaw ghetto from The Pianist in a documentary about WW2 ghettos to illustrate your point, it is much more likely that you could rely on the fair dealing exception for quotation.

Another factor to consider, when thinking about ‘fair dealing,’ is the proportion of the work that is used. The CDPA does not define what ‘no more than is required’ means exactly, but it is generally understood as the minimum amount of work that is needed to make a certain point. That is, if you want to quote from someone else’s film to make a point, you will very likely only have to show a short clip from that work to support your argument. However, depending on the circumstances, it may also be fair to quote a particular work in its entirety. For example, if you want to make use of a photograph for illustrative purposes in an historic documentary then it may well be fair to show the photograph in its entirety. This is what the IPO means with ‘it will always be a matter of fact, degree and impression in each case.’

The market for the original work is one of the other determining factors in considering whether a particular dealing is fair. It will not be considered fair if the new work can be seen as a substitute for the original and will threaten the commercial exploitation of the original work.

Finally, you should never forget that if the film material you want to make use of is out of copyright (that is, it is in the public domain), there is no need to rely on an exception or to seek permission from the former copyright owner. You can make use of material in the public domain without having to ask anyone’s permission.

FAIRNESS IN SPRINGFIELD

Section 31 of the CDPA addresses incidental inclusion of copyright material. That is, copyright in someone’s work is not infringed by its incidental inclusion in another work, such as an artistic work, a sound recording, a film or a broadcast. For example, you might be filming a scene on a busy street, and in the background of your shot is a poster for a new cinema release or an art exhibition. So long as the poster has not been deliberately included – that is, it is not the main focus of interest in the scene, or is of ‘secondary importance’ – there is no infringement.

Incidental inclusion only applies to ‘live-action’ material. For instance, it will not apply to animation in which everything on the screen is the result of deliberate decisions made by the filmmaker(s). Think about The Game is On! Nothing in these films has been incidentally included. If any aspect of other people’s work has been included, it has been included for a purpose. However, the idea that there can be no incidental inclusion in animation does not mean there is no incidental inclusion with animation. Consider the following example from the US.

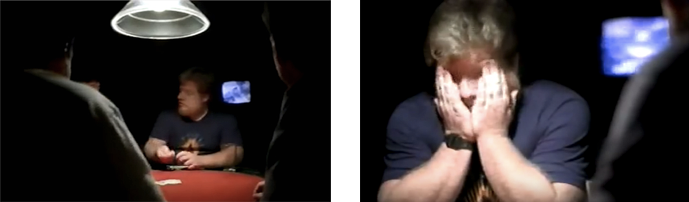

Sing Faster: The Stagehand’s Ring Cycle is a 1999 documentary by Jon Else about the stagehands at the San Francisco Opera during the production of Richard Wagner’s 17-hour Ring Cycle opera. To contrast the ‘high’ culture that is performed on stage with what the stagehands are doing backstage simultaneously, the filmmaker shows them playing cards and watching TV. The few seconds of an episode of (the highly recognisable) The Simpsons were shown on a television screen in the corner of the shot. The enormous amount of money that the rights holders wanted for permission to use the clip ($10,000 for 4 seconds) almost brought the documentary to a halt.

As we have seen in Case Files #2 and #21, copyright laws differ from country to country. Unlike the UK and other EU countries, US copyright law does not include an exhaustive list of specific copyright exceptions such as quotation or incidental inclusion. However, it does allow ‘fair use’ of another person’s work, a very general and open-ended exception. Section 107 of the US Copyright Act states that ‘the fair use of a copyrighted work for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching […], scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.’ The list of purposes included in the US fair use provision is not exhaustive, meaning that a conduct for any purpose may be fair use if it satisfies the requirement of fairness. The same section of the US Copyright Act provides a list of four factors to be considered in determining whether a particular use is fair:

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

At the time, the filmmakers of Sing Faster: The Stagehand’s Ring Cycle were advised that the inclusion of the clip from The Simpsons would probably qualify as fair use, but there was no guarantee that it would. Moreover, they were advised that Twentieth Century Fox, who own the copyright, would be likely to sue for infringement. Because of the risks involved, getting the required insurance for a distribution deal would have been difficult. So, the filmmakers needed to either pay the licensing fee, or not use the clip at all. In the end, they decided to replace the clip in the background with other, more generic and unrecognisable material.

If this film was made today in the UK, the filmmakers would likely be able to rely on the exception for incidental inclusion, or perhaps another copyright exception such as quotation, to ensure they could include the background footage in their documentary.

Stills from Sing Faster: The Stagehand’s Ring Cycle, on which The Simpsons cannot be seen in the background.

The Simpsons was also at the heart of another dispute. In that scenario, a clip from The Simpsons was used to back up an argument in the 2005 documentary Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, about the collapse of the Enron Corporation. The makers of The Simpsons had come up with an amusement park ride called Enron’s Ride of Broken Dreams. In the particular clip a group of people who believe that they will be rich plummet towards the ‘Poor House’. The documentary filmmakers wanted to use the clip as an indication of how Enron’s corporate scandal had made its way into popular culture.

In this case, the filmmakers decided to rely on the fair use defence. They considered that the purpose of the clip clearly served the intention of the film; they had used the minimum amount for their purpose, and the context of the material was changed while value was added. The clip was included in the documentary.

If this film was made today in the UK, the filmmakers would be able to rely on the fair dealing for quotation exception: the relevant requirements of the exception would likely be met, and the inclusion of the clip would likely not pose a problem.

Stills from an episode of The Simpsons, featuring the Enron’s Ride of Broken Dreams.

FOR DISCUSSION: TO ASK OR NOT TO ASK?

Do you think that the exceptions for fair dealing for quotation and incidental inclusion are helpful tools to documentary filmmakers?

Digitisation has made it very easy to duplicate material, and to include that material into your own work. Do you think there is a link between digitisation and fair dealing?

How would you react if it was your work that was included in someone else’s work? How would you establish whether they had relied on fair dealing in using your work?

USEFUL REFERENCES:

The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 is available here: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/contents

Chapter III (sections 28-76) sets out the Acts Permitted in relation to Copyright Works.

You can find lots of information about Copyright Exceptions in Chapter 7 of ‘Copyright 101’ of Copyright Cortex, available here: https://copyrightcortex.org/copyright-101/chapter-7

For an introduction into documentary film, see Patricia Aufderheide, Documentary Film. A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: OUP, 2007).

For a US-specific initiative, see the Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use, available here: http://cmsimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Documentary-Filmmakers.pdf

This statement is based on the study by Patricia Aufderheide and Peter Jaszi, for which they interviewed 45 filmmakers: Untold Stories: Creative Consequences of the Rights Clearance Culture for Documentary Filmmakers. (Washington, DC: Center for Social Media, American University, 2004).

Download the PDF version of Case File #2 – The Monster

Download the PDF version of Case File #5 – The Terrible Shark

Download the PDF version of Case File #6 – The Famous Pipe

Download the PDF version of Case File #21 – The Six Detectives

Download the PDF version of Case File #24 – The Retrieved Image

Download the PDF version of Case File #25 – The Accidental Image

More Case Files

22. The Two Heads

In this Case File #22 we consider the concepts of joint authorship and joint ownership of a copyright work.

23. The Eight Categories

In this Case File #23 The Eight Categories we consider the different categories of work that can be protected by copyright in the UK.

24. The Retrieved Image

This Case File #24 considers film as cultural heritage, the preservation exception for archive material, wider implications of preservation and restoration.

26. The Recorded Performance

In this Case File #26 we look at the protection conferred to actors and other performers by performers’ rights.

27. The Interview Tape

In this Case File #27 we look at the different types of rights that may be ‘caught’ in the recording of interviews.