23. THE EIGHT CATEGORIES

Holmes and Watson are being interviewed and filmed at the same time. When the mysterious interviewer asks Sherlock to ‘please sit down’, we see him appearing in different parts of the room assuming various postures. We adopted this editing technique – known as ‘jump cutting’ – to refer to a famous case concerning a film: Norowzian v. Arks Ltd (1999).

Filming an interview of someone will often simply involve setting up a single camera, getting it in the right position, checking the sound levels, and then pressing record. The film of the interview is protected by copyright. However, making a movie such as The Forger’s Apprentice will involve various works created by different people and protected by copyright, such as texts, images and music.

In this Case File #23 we consider the different categories of work that can be protected by copyright in the UK, as well as whether the same work might sit in more than one category at the same time.

EIGHT CATEGORIES OF COPYRIGHT WORK

The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (the CDPA) sets out a list of eight different types of work protected by copyright (s.1). These are:

– original literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works (s.1(1)(a))

– sound recordings, films and broadcasts (s.1(1)(b))

– the typographical arrangement of published editions (s.1(1)(c))

While all eight types of protected subject matter are referred to in the legislation as ‘works’, it is important to appreciate that more than one copyright may exist in a single cultural product or creation. For example, a recording of a song: there may be copyright in the lyrics, in the music, in the arrangement, and in the sound recording itself. With a film, there may be copyright in the original story, in the screenplay (as a dramatic work), in the musical score, as well as in the film (as a recording). It is important to be able to identify the different types of copyright that may be involved as each may have a different author and/or owner.

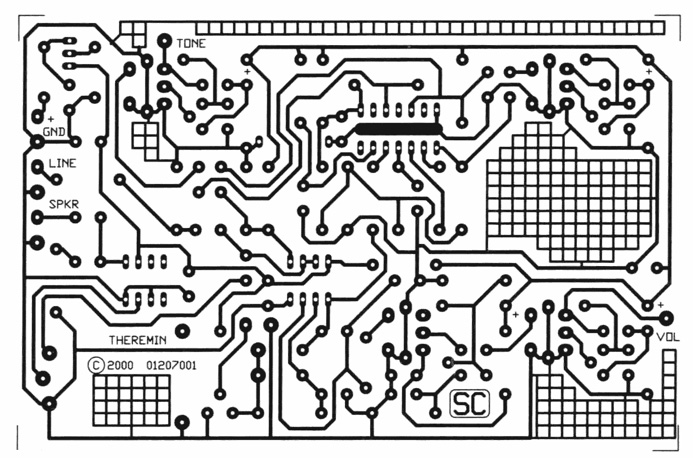

One question left open by the CDPA is whether the same work might fall into two different categories at the same time. Consider the printed circuit board (PCB) layout for a musical instrument below. The layout is transferred onto a sheet of copper and then etched so only copper remains under the black lines to form connections between components mounted through holes which are drilled where there are circles.

The author claims that it is copyright protected (see the bottom left-hand corner of the diagram). But what kind of copyright work is it? It conveys information and provides a set of instructions that can be read by people skilled in the manufacture of PCBs, so it could be considered a literary work. Similarly, it could be considered as a network, listing interconnections between components (known as a net list). Or, is it an artistic work? It certainly has an obvious artistic aesthetic and appeal. Or perhaps it is both a literary work and an artistic work?

Would infringement occur if the position of the components were changed but the circuit had the same connections (net list) but looked visually different? What about when the PCB is manufactured? Is it a 3d reproduction of a 2d literary work or is it a 3d reproduction of an

artistic work and does it matter?

Whether something can fall into two different categories of copyright-protected work at the same time was considered in Norowzian v. Arks Ltd (1999): this case concerned a film.

THE CASE: NOROWZIAN v. ARKS LTD (1999)

In Norowzian v. Arks Ltd (1999) the claimant had made a short film, Joy, with a single dancer as the protagonist. The film had no dialogue and made use of an editing technique referred to as ‘jump cutting’.

Arks, who were the advertising agents for the Guinness group, approached Norowzian to make an ad campaign entitled Anticipation, influenced by Joy. Norowzian refused; Arks made their ad campaign anyway (you can watch the advert here).

Because Arks had not included any actual footage from Joy in their advert, Norowzian was not able to claim copyright infringement in his film as a film. Instead, however, he argued that in producing an advert influenced by Joy, Arks had infringed the copyright in his film as a dramatic work.

Under the CDPA, a film is defined as a recording on any medium from which a moving image may be produced by any means (s.5B(1)), a broad definition which encompasses celluloid films, video recordings, disks, and so on. In addition, the CDPA defines a dramatic work as including ‘a work of dance or mime’ (s.3(1)).

In the High Court, the judge held that Joy could not be a recording of a dramatic work as the editing technique employed created a visual image that could not be recreated in the real world. That is, a work of dance or mime had to be capable of being performed.

In the Court of Appeal, however, it was held that the expression ‘dramatic work’ should be given its ordinary and natural meaning, which was a work of action, with or without words or music, which was capable of being performed before an audience. The court continued that a film could be both a recording of a dramatic work but also a dramatic work in that it was a work of action that was capable of being performed before an audience.

In other words, a film might be protected by copyright as a film and as a dramatic work: that is, it could fall into two of the eight different categories of work protected by copyright.

CURIOSITY: FILMS MADE BEFORE 1 JUNE 1957

Whereas the 1988 CDPA protects eight different categories of work, earlier copyright acts did not. For example, under the 1911 Copyright Act copyright was not granted to a film as such. Instead, films were either protected as if they were a series of photographs (for non-fiction and documentary films), or they were protected as if they were a dramatic work, like a play (fiction films).

This had an important consequence for duration of protection in films at that time. That is, under the 1911 Act fiction films (as dramatic works) were protected for the life of the author of the film (at that time, the director) plus 50 years. By contrast, non-fiction and documentary films were protected (as photographs) for 50 years from the year in which they were made.

Under the CDPA today, certain types of films still only receive 50 years protection from the end of the year in which the film was made. Read Case File #22 to find out more.

FOR DISCUSSION: LIFE IS A DRAMA (OR MAYBE A FILM) (OR MAYBE BOTH)

In general, the fact that a film might fall within two different categories of protected work – as a film and as a dramatic work – does not give rise to many contradictions or problems, in that both types of work enjoy the same economic and moral rights. One difference, however, concerns duration of protection.

Read Case File #22 and try to answer the following questions:

– under the CDPA, if a film is protected as a dramatic work who is the author of that work (as defined in law)?

– if a film is also protected as a film, who is that author of that film (as defined in law)?

Now ask yourself:

– how is duration of copyright protection calculated in relation to the film as a dramatic work?

– how is duration of copyright protection calculated in relation to the film as a film?

Do you think the law is too complicated? Does it make sense? What steps could be taken to simplify the law of copyright in relation to the protection of films?

USEFUL REFERENCES:

Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/contents

Norowzian v. Arks Ltd [1999] EWCA Civ 3018

For further information on copyright duration in the UK, see Copyright Bite #1 – Copyright Duration: https://www.copyrightuser.org/create/public-domain/copyright-bite-1-duration/

Download the PDF version of Case File #22 – The Two Heads

Download the PDF version of Case File #23 – The Eight Categories

More Case Files

22. The Two Heads

In this Case File #22 we consider the concepts of joint authorship and joint ownership of a copyright work.

24. The Retrieved Image

This Case File #24 considers film as cultural heritage, the preservation exception for archive material, wider implications of preservation and restoration.

25. The Accidental Image

In this Case File #25 we explore the relationship between documentary filmmaking, the re-use of other people’s work and copyright exceptions.

26. The Recorded Performance

In this Case File #26 we look at the protection conferred to actors and other performers by performers’ rights.

27. The Interview Tape

In this Case File #27 we look at the different types of rights that may be ‘caught’ in the recording of interviews.