5. THE TERRIBLE SHARK

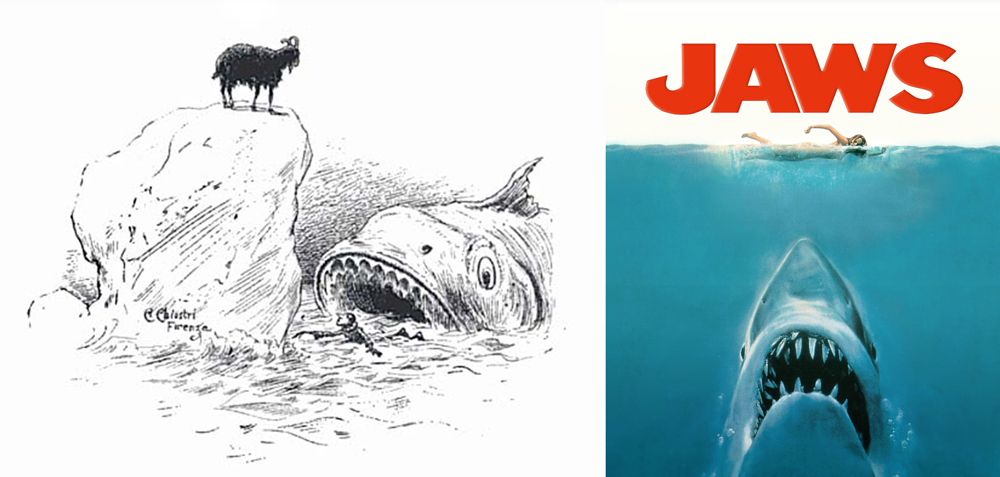

This illustration from our video depicts a terrible shark-like creature about to eat Joseph’s toy. It was inspired by two different images: an illustration of the ‘Terrible Shark’ by Carlo Chiostri (1863 – 1939), from one of the first editions of Carlo Collodi’s (1826 – 1890) The Adventures of Pinocchio, and a theatrical release poster for Steven Spielberg’s classic film Jaws (1975).

While the former is in the public domain because Chiostri died more than 70 years ago, the poster for Jaws is still in copyright. So, if you want to copy the artwork from the Jaws poster you need to ask for the copyright owner’s permission unless, that is, you can rely on one of the exceptions to copyright.

This Case File #5 demonstrates that you are free to make use of a copyright work, without seeking the owner’s permission, if your use falls within one of the copyright exceptions.

COPYRIGHT EXCEPTIONS

UK copyright law provides for a number of exceptions to copyright, specific circumstances when work can be used without the need to get permission from the copyright owner. There are a number of copyright exceptions set out in the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, concerning non-commercial research and private study, quotation, news reporting, education, and other uses.

A number of these exceptions are sometimes referred to as ‘fair dealing’ exceptions because the law often requires that your use of the material for that particular purpose must be fair. Indeed, each copyright exception has specific requirements about how and when the material can be used without permission, and in order to benefit from an exception you must make sure you fulfil the relevant requirements.

For our illustration above, we have relied on the exception for Caricature, Parody or Pastiche in referencing the iconic artwork for the Jaws poster.

CARICATURE, PARODY AND PASTICHE

To parody a work is to use it a humorous way to make a particular point. This might be to make a comment on the work that you have parodied, or you might be making fun of, criticising or drawing attention to a different work or issue altogether.

Before October 2014, creating a parody of a copyright work in the UK would typically have been considered copyright infringement. However, with the introduction of a new exception for parody, copyright material can now be parodied without the permission of the owner, in certain circumstances. Specifically, your use of the copyright work must be fair.

How much copying from a work is fair or unfair is an issue ultimately decided by a court of law on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the interests and rights of the owner as well as the freedom of expression of the person relying upon the parody exception. In making this decision, a court will typically take a number of different factors into account, such as the amount of the work that has been copied.

As the exception is new, the government have produced guidelines to help owners and users understand what it means in practice. The government’s guidance is available here. It suggests that you should only make a limited or moderate use of someone else’s work to create your parody. For example, it is unlikely to be considered ‘fair’ to use an entire musical track, without any alteration or change, to create a spoof video to post online. If you are using someone else’s work in its entirety, you should almost certainly get permission from the owner.

On the other hand, there are plenty of circumstances under which the new exception can be relied upon: a comedian using a few lines from a film or song for a parody sketch; a cartoonist referencing a well-known artwork or illustration for a caricature; or an artist using small fragments from a range of films to compose a larger pastiche artwork.

We have parodied the poster from Jaws to make the point that parody is now lawful under the UK copyright regime. What do you think? Can we rely on the new exception? Is our use fair?

For more information on the exception for caricature, parody and pastiche, see the copyrightuser.org page here.

THE CASE: Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp v Anglo-Amalgamated Film Distributors [1965] 109 SJ 107

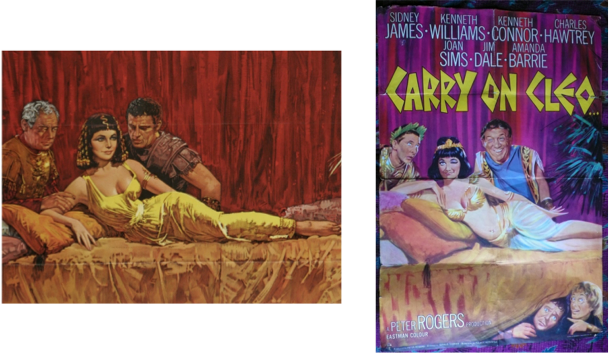

This case also concerned movie posters. The defendants created a poster for their film Carry on Cleo that was based on the artwork for Twentieth Century Fox Film’s film Cleopatra starring Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor. The judge decided that as ‘the defendant’s poster reproduce[d] a material part of [Twentieth Century’s] poster’, their use amounted to substantial copying and so infringed the copyright in the original work. On this basis the judge granted an injunction against the second work, stopping the defendants from distributing or displaying their poster.

FOR DISCUSSION: A CLEOPATRA FOR THE 21st CENTURY?

As mentioned, in October 2014 new copyright exceptions were introduced into UK copyright law. One of the new exceptions permits the use of copyright material for the purposes of parody. The Cleopatra case, referred to above, was decided before the introduction of this exception, but what if the case were decided today? The defendants would certainly argue that their use fell within the exception for parody. Do you think they would be successful? Is their work really a parody? Is it fair? Does it matter that they were parodying the work for their own commercial purposes?

Do you think the law today strikes a better balance between the rights of copyright owners and the interests of the general public, compared to the law before an exception for parody was introduced?

Download the PDF version of Case File #5 – The Terrible Shark.

More Case Files

1. The Red Bus

The Adventure of the Girl with the Light Blue Hair starts with a red double-decker bus travelling across Westminster Bridge, with the Houses of Parliament in the background.

2. The Monster

One of the graffiti that scare the toymaker Joseph portrays a monster eating his ‘beautiful, wonderful toy’. The image of the monster is inspired by two different artistic works

3. The Baker Street Building

Sherlock Holmes and John Watson discuss Joseph’s case at 221B Baker Street. The above illustration is inspired by two sources…

4. The Anonymous Artist

Joseph, the toymaker, has asked the police to identify the culprit making ‘dreadful images’ of his toy, portraying it in violent situations.

6. The Famous Pipe

The pipe has been associated with the image of Sherlock Holmes since Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s (1859 – 1930) stories were first published in The Strand Magazine with illustrations by Sidney Paget (1860 – 1908).

7. The Matching Wallpaper

In the background of Holmes and Watson’s apartment you can see wallpaper with ‘flowers scattered over it in a somewhat impressionistic style’.

8. The Dreadful Images

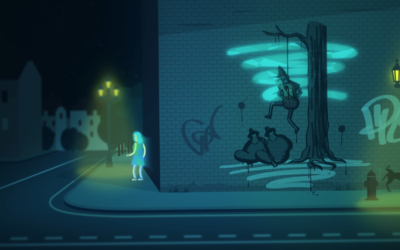

The ‘dreadful images’ that scare Joseph, the toymaker, are graffiti drawn all over the ‘fictional land called London’. The illustration above, depicting Joseph’s toy hung from a tree, is based on an actual place in London.

9. The Improbable Threat

In trying to persuade Holmes to take Joseph’s case, Watson asks: ‘What if it’s a threat? That’s what the graffiti might mean.’ These eleven words are based on dialogue from The Blind Banker…

10. The Uncertain Motivation

Joseph, Sherlock Holmes and the Girl with the Light Blue Hair are all creators: Joseph draws and designs toys; Sherlock composes music; and the mysterious girl is an accomplished street artist.

11. The Mutilated Work

In trying to persuade Holmes to take the case, Watson argues that: ‘If you were a professional musician, you wouldn’t want people copying or mutilating your work’.

12. The Hollywoodland Deal

Joseph explains to Holmes and Watson when and why the dreadful images of his beautiful, wonderful toy began to appear all over London. When ‘some guys’ from Hollywoodland approached him ‘to option a movie’…