7. THE MATCHING WALLPAPER

In the background of Holmes and Watson’s apartment you can see wallpaper with ‘flowers scattered over it in a somewhat impressionistic style’.

There is a famous copyright case involving the design of two different wallpapers: Designer Guild Limited v Russell Williams (Textiles) Limited [2000] UKHL 58. In this case, the judge identifies seven points of similarity between the claimant’s wallpaper and the defendant’s infringing copy. We gave our illustrator Davide Bonazzi the same seven points as a guideline for creating the wallpaper in our video.

This Case File #7 offers points of discussion about fundamental copyright concepts, such as the difference between an idea and the expression of an idea, and what it means to copy a substantial part of an existing work. The Case File also reminds us that judges do not always agree on how these issues should be resolved, or whether a particular instance of copying is unlawful or not.

IDEA AND EXPRESSION

When creating new work it is natural to be inspired by the work of others. Indeed, one of the ways that copyright promotes the creation of new work and the spread of knowledge is by providing authors with rights in their work while, at the same time, allowing the public to make use of that work in certain ways.

One way in which copyright does this is by protecting only the expression of ideas and not ideas themselves. This means that the idea or ideas for a song, a novel, or a painting are free for anyone to use and take inspiration from. But what you cannot copy is the original way an author has expressed his or her idea(s) in that song, that novel, or that painting. In this way creators are given the opportunity to benefit from their own personal expression, while the general ideas underpinning a work remain available for others to use.

However, it is not always easy to draw the line between the lawful borrowing of simple ideas and when borrowing becomes unlawful because you have copied, for example, too many ideas from the plot of a play or a film, or have copied just one or two ideas but in too much detail.

So, feel free to be inspired by other people’s ideas but make sure you bring something new to those ideas and express them in your own individual way.

For an interesting video on copyright and the balance between protecting creative works and allowing the public to use them click here.

SUBSTANTIAL TAKING

Infringement of a copyright work occurs when the whole or a substantial part of a protected work is used without permission or without the benefit of a copyright exception. Therefore, taking an insubstantial part of a copyright work without permission is allowed. This is because the law recognises that no real injury is done to the copyright owner if only an insignificant part of the work is copied.

Under UK copyright law substantial taking is considered by the courts to be a matter of quality, not quantity. So it is not just about how much you copy from someone else’s work, it is about the importance of the parts that you take from that work. This makes it difficult to define exactly what amounts to a substantial part of a work.

For example, copying one table or a graph from a textbook on mathematics might be regarded as substantial copying – even though it is only one from hundreds of pages – on the basis that it took considerable effort to produce and that it conveys a lot of important information in a simple and easily digested form.

In one case making use of 50 seconds of a song was found to be a substantial part because that particular part was recognisable by the public. The 50-second sequence within the song does not need to have copyright protection in its own right, but, taken as a whole, it was understood by the courts to be a substantial part of the work.

THE CASE: Designer Guild Limited v Russell Williams [2000] UKHL 58

Designer Guild (the claimant’s work) |

Russell Williams (the defendant’s work) |

In this case the claimant, Designer Guild, designed and manufactured fabrics and wallpapers. One of their wallpaper designs, called the Ixia, had been inspired by the work of the French impressionist painter Henri Matisse and was a great commercial success. Designer Guild sued Russell Williams for copying the Ixia design. The defendants denied any copying.

Identifying seven similarities between the two wallpapers, the trial judge held the defendant had copied the Ixia design, and that the copying was substantial.

Russell Williams appealed, arguing that if there was copying they had not copied a substantial part of the claimant’s work. The Court of Appeal agreed and overturned the trial judge’s decision: the court considered that while the defendant had borrowed ideas and artistic techniques from the Ixia design, their copying had not been substantial. One of the Court of Appeal judges said the wallpapers ‘just do not look sufficiently similar’.

Designer Guild then appealed to the House of Lords (what is now referred to as the Supreme Court). On a technical point of law, the House of Lords unanimously agreed to overturn the Court of Appeal’s decision and reinstate the trial judge’s original ruling: the defendant had infringed the claimant’s copyright.

However, a number of the judges in the House of Lords did also say they thought the defendant’s copying had been substantial. Lord Hoffman commented that substantial copying did not have to involve literal copying. One could infringe copyright by copying a particular feature or a combination of features from someone’s work without slavishly copying the work itself. He also pointed out that it was irrelevant whether the defendant’s wallpaper looked like the claimant’s wallpaper: all that mattered was whether a substantial part of the original work had been copied.

A CASE OF INDIRECT COPYING?

As we mentioned, we gave our illustrator Davide Bonazzi the same seven points of similarity from the Designer Guild case as a guideline for creating the wallpaper in our video. For example, we asked Davide to produce a design consisting of ‘vertical stripes, with spaces between the stripes equal to the width of the stripe’, with flowers and leaves ‘scattered over and between the stripes’, and that the centre of the flower heads should be represented by ‘a strong blob, rather than by a realistic representation’.

When Davide created his wallpaper design he had never heard of the Designer Guild case (we didn’t tell him about it) and he had never seen the wallpaper designs from the case.

But in producing a design in accordance with the seven points of similarity, has Davide created a work that potentially infringes the Designer Guild wallpaper? Can you copy a work without ever having seen it simply by following a set of instructions describing the essential features of that work?

FOR DISCUSSION: THE SIMILAR AND THE DIFFERENT

One of the Court of Appeal judges commented that the wallpapers ‘just do not look sufficiently similar’ whereas one of the judges in the House of Lords said that ‘they looked remarkably similar to me.’

What do you think? Do you think the two wallpaper designs look similar? Does it matter whether they look similar?

As explained there were three different decisions taken in this case, with different judges taking different views on whether the defendant’s copying was substantial and so infringing. Copyright litigation often involves borderline decisions about which reasonable people might disagree. Ultimately, though, the decision of the House of Lords (or what is now the Supreme Court) is the most important. It takes precedence.

What do you think about the different decisions in this case? Do you think that the Court of Appeal or the House of Lords made the decision in the correct way? Why is it challenging for courts determine copyright infringement in something like wallpaper?<

USEFUL REFERENCES:

Designer Guild Limited v Russell Williams (Textiles) Limited (Trading As Washington Dc) [2000] UKHL 58 is available here.

Download the PDF version of Case File #7 – The Matching Wallpaper.

More Case Files

1. The Red Bus

The Adventure of the Girl with the Light Blue Hair starts with a red double-decker bus travelling across Westminster Bridge, with the Houses of Parliament in the background.

2. The Monster

One of the graffiti that scare the toymaker Joseph portrays a monster eating his ‘beautiful, wonderful toy’. The image of the monster is inspired by two different artistic works

3. The Baker Street Building

Sherlock Holmes and John Watson discuss Joseph’s case at 221B Baker Street. The above illustration is inspired by two sources…

4. The Anonymous Artist

Joseph, the toymaker, has asked the police to identify the culprit making ‘dreadful images’ of his toy, portraying it in violent situations.

5. The Terrible Shark

This illustration from our video depicts a terrible shark-like creature about to eat Joseph’s toy. It was inspired by two different images…

6. The Famous Pipe

The pipe has been associated with the image of Sherlock Holmes since Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s (1859 – 1930) stories were first published in The Strand Magazine with illustrations by Sidney Paget (1860 – 1908).

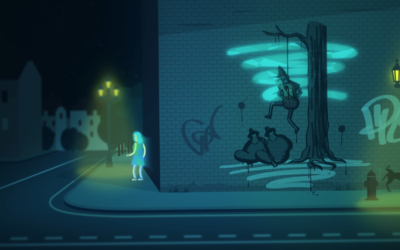

8. The Dreadful Images

The ‘dreadful images’ that scare Joseph, the toymaker, are graffiti drawn all over the ‘fictional land called London’. The illustration above, depicting Joseph’s toy hung from a tree, is based on an actual place in London.

9. The Improbable Threat

In trying to persuade Holmes to take Joseph’s case, Watson asks: ‘What if it’s a threat? That’s what the graffiti might mean.’ These eleven words are based on dialogue from The Blind Banker…

10. The Uncertain Motivation

Joseph, Sherlock Holmes and the Girl with the Light Blue Hair are all creators: Joseph draws and designs toys; Sherlock composes music; and the mysterious girl is an accomplished street artist.

11. The Mutilated Work

In trying to persuade Holmes to take the case, Watson argues that: ‘If you were a professional musician, you wouldn’t want people copying or mutilating your work’.

12. The Hollywoodland Deal

Joseph explains to Holmes and Watson when and why the dreadful images of his beautiful, wonderful toy began to appear all over London. When ‘some guys’ from Hollywoodland approached him ‘to option a movie’…