11. THE MUTILATED WORK

In trying to persuade Holmes to take the case, Watson argues that: ‘If you were a professional musician, you wouldn’t want people copying or mutilating your work’.

UK copyright law gives creators both economic rights and moral rights. While ‘copying’ someone else’s work without permission may constitute an infringement of their economic rights (such as the reproduction right or the right of communication to the public), ‘mutilating’ it might infringe the creator’s moral rights. In the UK, moral rights include the right to be identified as the author of the work (the right of attribution) and the right not to have your work subjected to ‘derogatory treatment’ (the right of integrity).

This Case File #11 considers the two principal moral rights held by creators in the UK, and investigates why it can be difficult to determine what amounts to ‘derogatory treatment’.

MORAL RIGHTS

Moral rights are concerned with the non-economic rights of a creator. They protect the creator’s connection with a work as well as the integrity of the work. The two principal moral rights in the UK are the right of attribution (sometimes referred to as the right of paternity) and the right of integrity (or the right to object to derogatory treatment).

Unlike economic rights, which can be licensed or assigned to another person, moral rights remain with the creator of the work and cannot be exercised by anyone else. However, creators can waive their moral rights if they so wish.

In some EU countries, such as France, moral rights last indefinitely. In the UK, however, moral rights are finite. That is, the right of attribution and the right of integrity last only as long as the work is in copyright. When the copyright term comes to an end, so too do the moral rights in that work. This is just one reason why the moral rights regime within the UK is often regarded as weaker or inferior to the protection of moral rights in continental Europe and elsewhere in the world.

RIGHT OF ATTRIBUTION

The right of attribution provides the creator of certain types of work with the right to be identified as the author of their work, so long as the creator has asserted his or her right.

The right of attribution covers works of literature, drama, music, art and films, and generally applies whenever the work is published commercially, performed in public or communicated to the public. However, there are a number of exceptions to this basic rule. For example, the right of attribution does not apply to works created for the purpose of reporting current events, contributions to newspapers, magazines and periodicals, works owned by the Crown or Parliament, or computer programs and computer generated work.

Also, the right of attribution does not arise unless it has been asserted by the creator of the work. In practice, a statement such as the example given below is often included in published work in order to make clear that the creator has asserted their moral rights:

‘The right of Joseph the Toymaker to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.’

RIGHT OF INTEGRITY

The right of integrity allows the creator to object to derogatory treatment of his or her work, or any part of it.

Like the right of attribution, the integrity right covers works of literature, drama, music, art and film. Similarly, the right of integrity does not apply to works created for the purpose of reporting current events, contributions to newspapers, magazines and periodicals, or computer programs and computer generated work. However, unlike the right of attribution, the integrity right does not need to be asserted.

Subjecting something to a derogatory treatment means adding to, deleting from, altering or adapting the work in such a way that it amounts to a distortion or mutilation of the work, or is otherwise prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the creator. Put another way, the right to integrity stops other people from modifying an author’s work in a way that may have a negative effect on the author’s reputation.

This does not mean that all forms of addition, deletion, alteration or adaptation will amount to a derogatory treatment.

For one thing, the law specifically provides that certain types of treatment fall outside the scope of the right. For example, translations of literary and dramatic works do not infringe the right of integrity, nor does simply arranging or transcribing a musical work into another register or key.

Also, your treatment of the work must be derogatory in that it is prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the person who created the work. But as we shall see, establishing prejudice to honour or reputation is not always straightforward.

THE CASE: Confetti Records v Warner Music UK Ltd [2003] EMLR 35

This case involved a piece of garage music composed by Mr Andrew Alcee, titled ‘Burnin’, which he sold to Confetti Records. Confetti Records arranged to license the song to the defendant, Warner Music UK Ltd. Warner Music produced an album including a rap version of Mr Alcee’s song by The Heartless Crew in which the band overlaid lyrics containing various references to violence and drug culture. In turn, Mr Alcee complained that his right of integrity in the music had been infringed.

Mr Alcee complained that the words overlaying his music glorified violence and drug culture. However, one problem he faced in establishing his case was that, when played at normal speed, the words of the rap were very hard to decipher. And even when played at half speed, it was not always clear what the phrases were, or what they meant. In short, if the lyrics could not be understood, it was difficult for Mr Alcee to claim that they were damaging to his reputation.

Another problem concerned evidence of harm to reputation. The court made clear that merely distorting or mutilating a work did not infringe the right of integrity unless the author could show prejudice to his honour or reputation. ‘However,’ the judge commented, ‘it seems to me that the fundamental weakness in this part of the case is that I have no evidence about Mr Alcee’s honour or reputation. I have no evidence of any prejudice to either of them.’ In the absence of any evidence that Mr Alcee’s honour or reputation had been harmed, the judge was not prepared to find that his right of integrity had been infringed.

FOR DISCUSSION: DEROGATORY OR NOT, WHO DECIDES?

In some countries, determining whether the right of integrity has been infringed depends on the subjective view of the author. That is, the courts will generally be guided by the author’s assessment in deciding whether the work in question has been subjected to a derogatory treatment.

In the UK, however, the courts have preferred a more objective approach. So, it is not sufficient that the author is annoyed or aggrieved by what has occurred. Instead the court must be convinced that a reasonable and objective person would regard the treatment as derogatory and damaging to the author’s reputation.

Did the court come to the right decision on Mr Alcee’s claim regarding his right of integrity? Should the courts take a subjective or a more objective approach regarding infringement of the integrity right?

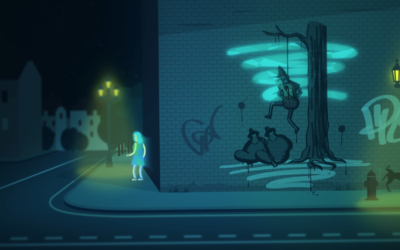

Having watched the video, do you think that by portraying Joseph’s toy hanging from a tree, the street artist has infringed Joseph’s moral rights? Do the graffiti amount to a derogatory treatment of Joseph’s copyright work? Is some of the graffiti more derogatory than the other?

USEFUL REFERENCES:

Confetti Records v Warner Music UK Ltd [2003] EMLR 35

The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 is available here. Sections 77-83 set out the scope of the right of attribution and the right of integrity.

Download the PDF version of Case File #11 – The Mutilated Work.

More Case Files

1. The Red Bus

The Adventure of the Girl with the Light Blue Hair starts with a red double-decker bus travelling across Westminster Bridge, with the Houses of Parliament in the background.

2. The Monster

One of the graffiti that scare the toymaker Joseph portrays a monster eating his ‘beautiful, wonderful toy’. The image of the monster is inspired by two different artistic works

3. The Baker Street Building

Sherlock Holmes and John Watson discuss Joseph’s case at 221B Baker Street. The above illustration is inspired by two sources…

4. The Anonymous Artist

Joseph, the toymaker, has asked the police to identify the culprit making ‘dreadful images’ of his toy, portraying it in violent situations.

5. The Terrible Shark

This illustration from our video depicts a terrible shark-like creature about to eat Joseph’s toy. It was inspired by two different images…

6. The Famous Pipe

The pipe has been associated with the image of Sherlock Holmes since Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s (1859 – 1930) stories were first published in The Strand Magazine with illustrations by Sidney Paget (1860 – 1908).

7. The Matching Wallpaper

In the background of Holmes and Watson’s apartment you can see wallpaper with ‘flowers scattered over it in a somewhat impressionistic style’.

8. The Dreadful Images

The ‘dreadful images’ that scare Joseph, the toymaker, are graffiti drawn all over the ‘fictional land called London’. The illustration above, depicting Joseph’s toy hung from a tree, is based on an actual place in London.

9. The Improbable Threat

In trying to persuade Holmes to take Joseph’s case, Watson asks: ‘What if it’s a threat? That’s what the graffiti might mean.’ These eleven words are based on dialogue from The Blind Banker…

10. The Uncertain Motivation

Joseph, Sherlock Holmes and the Girl with the Light Blue Hair are all creators: Joseph draws and designs toys; Sherlock composes music; and the mysterious girl is an accomplished street artist.

12. The Hollywoodland Deal

Joseph explains to Holmes and Watson when and why the dreadful images of his beautiful, wonderful toy began to appear all over London. When ‘some guys’ from Hollywoodland approached him ‘to option a movie’…