Data scraping or mining and protected databases

Protection of a dataset is contextual in every case – the data, database and other context may dictate higher or lower risk for data scraping and data mining. Even where an exception permits use in one context (for example, a copyright exception for text and data mining), other types of protection must be considered.

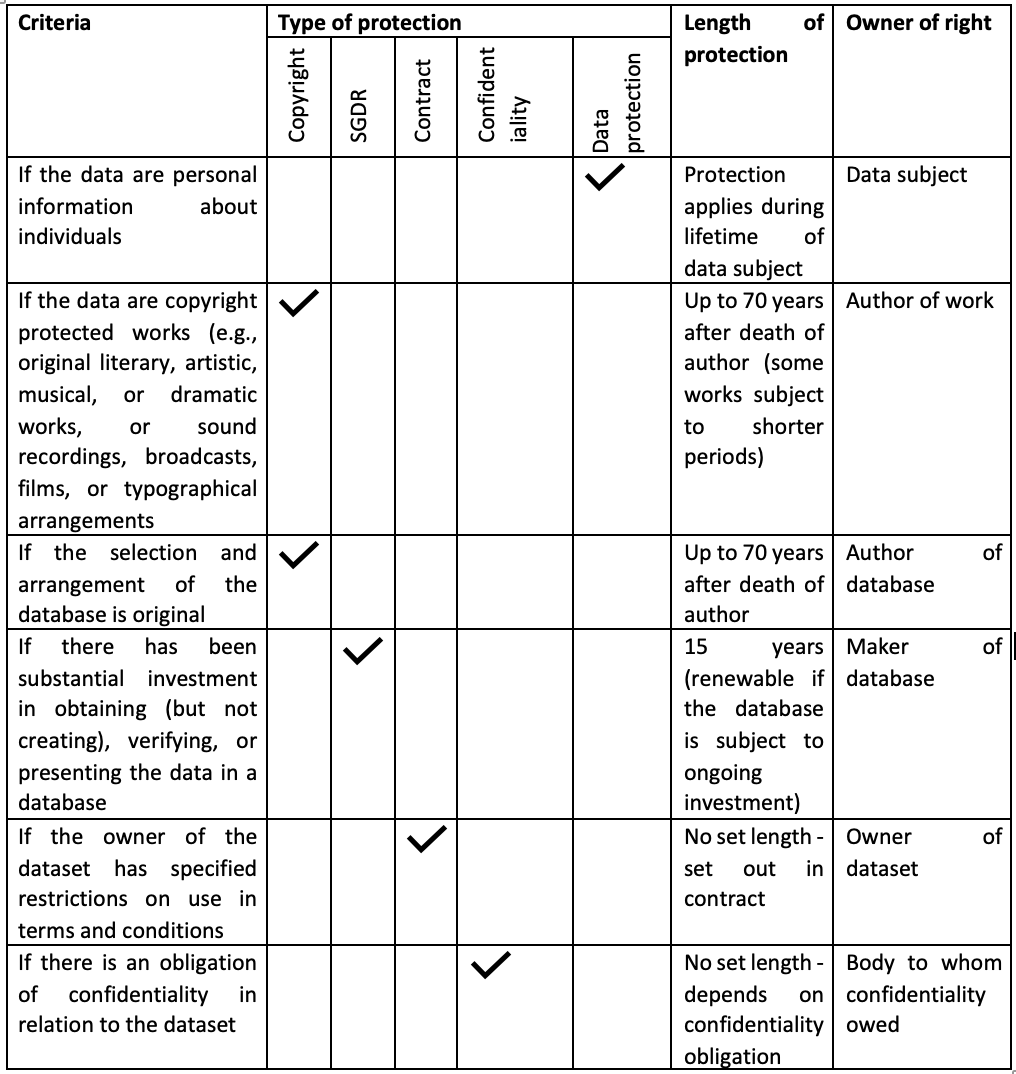

The table below shows how data in a dataset might be protected (concurrently):

| Criteria | Type of protection | Duration | Owner | ||||

| Copyright | SGDR | Contract | Confidentiality | Data protection | |||

| If the data are personal information about individuals | ✔ | Protection applies during lifetime of data subject | Data subject | ||||

| If the data are copyright protected works (e.g. original literary, artistic, musical or dramatic works, or sound recordings, broadcasts, films or typographical arrangements | ✔ | Up to 70 years after death of author (some works subject to shorter periods) | Author of work | ||||

| If the selection and arrangement of the database is original | ✔ | Up to 70 years after death of author | Author of database | ||||

| If there has been substantial investment in obtaining (but not creating), verifying or presenting the data in a database | ✔ | 15 years (renewable if the database is subject to ongoing investment) | Maker of database | ||||

| If the owner of the dataset has specified restrictions on use in terms and conditions | ✔ | No set length – set out in contract | Owner of dataset | ||||

| If there is an obligation of confidentiality in relation to the dataset | ✔ | No set length -depends on confidentiality obligation | Body to whom confidentiality owed | ||||

The sui generis database right (SGDR)

The SGDR was a special right deliberately created to protect the investment in databases, for which there are no other forms of protections for the data in them.

Confusingly, the SGDR applies when there has been ‘substantial investment’ (which can be financial, human, technical or risk based investment) in “obtaining, verifying or presenting the contents” of a database, but the courts have decided that the SGDR does not apply when the data itself is actually created. For example, creating football fixture lists from scratch does not merit SGDR protection, but putting together fixtures lists created by others might be considered to be ‘obtaining’ data.

It is not always obvious to a data user whether a database contains data that has been created, obtained, verified or presented and how substantial the investment in a database has been. This makes SGDR protection a risk for all those engaging in data scraping and data mining to consider.

The SGDR prevents extraction or re-utilisation of all or a ‘substantial’ part of the contents of a database – unless permission is given. It can apply where insubstantial parts of a database are repeatedly extracted or re-utilised. This right therefore has the scope to prevent data scraping (extraction) and data mining (re-utilisation). A limited number of exceptions apply.

Exceptions to the SGDR

The exceptions to the SGDR are summarised below. They are limited in scope and do not provide a general right to conduct data scraping or data mining.

| When Exception applies | Right to Extraction | Right to Reutilisation | Conditions |

| ‘the purpose of illustration for teaching or research and not for any commercial purpose’ | Yes | No |

· Already available to the public · Fair dealing · Lawful user · Attribution of source |

| ‘copying [of a work from the internet] by a deposit library or a person acting on its behalf’ Deposit Libraries | Yes | No |

· Connection with UK · Compliance with conditions set out in the Legal Deposit Libraries Act 2003 |

| ‘making of an accessible copy of a work [by a disabled person or authorised body] for the benefit of a Marrakesh beneficiary’ | Yes | No |

· Personal use of a disabled person · Authorised bodies on a not-for-profit basis |

| ‘anything done for the purposes of parliamentary or judicial proceedings or for the purposes of reporting such proceedings’ | Yes | Yes | |

| Royal Commission, Statutory Inquiry or reports from the same | Yes | No | |

| Database is open to public inspection or is a statutory register | Yes | No |

· Factual information · With authority of the ‘appropriate person’ |

| Database is open to public inspection | Yes | Yes |

· With authority of the ‘appropriate person’ · purpose of enabling the contents to be inspected at a more convenient time or place |

| Database is open to public inspection and the contents ‘contain information about matters of general scientific, technical, commercial or economic interest’ | Yes | Yes |

· With authority of the ‘appropriate person’ · Purpose of disseminating that information |

| ‘contents of a database have in the course of public business been communicated to the Crown for any purpose, by or with the licence of the owner of the database right and a document or other material thing recording or embodying the contents of the database is owned by or in the custody or control of the Crown.’ | Yes | Yes |

· Applies to Crown only · No prior publication |

| Database is comprised in public records open to public inspection | Yes | Yes |

· Public records · Authority of officer under Public Records legislation |

| Act is specifically authorised by Act of Parliament | Yes | Yes | · Act of Parliament |

Permission or an exception is required to make use of a SGDR protected database lawful.

Many governmental agencies as well as academic and research institutions adopt open access policies and practices and make their resources freely available to use. The UK data service, for example, is open access and some of their collections are open data. The open access initiative in the Netherlands aims to grant free and open online access to academic data and publications. Google Scholar, Internet Archive, and Wikimedia Commons are examples of open access databases.

Making data ‘open’ is a form of collective licensing that can make use of otherwise SGDR protected datasets lawful.

Contractual restrictions

When data scraping or mining, bear in mind that the owner of the dataset might have made access to the dataset subject to general or specific contractual restrictions (for example, available under ‘terms and conditions’). This might prohibit data scraping or mining completely, or only allow it for non-commercial purposes. Such restrictions can apply even if the data or database isn’t protected by copyright, data protection law or the SGDR. In fact, because some copyright and SGDR exceptions cannot be contracted out of, contract law is even more successful in protecting data which is not subject to copyright and SGDR protection.

In 2015 a commercial airline company successfully sought legal remedy against a company that was data scraping from its website for its own price comparison site. The pricing data itself did not attract protection, as it was not original, nor did the website attract SGDR protection, as there had not been a substantial investment in obtaining, verifying and presenting the data – it was a simple pricing and booking system. However, the website’s terms and conditions specified that data scraping was not a permitted use, and the court upheld this restriction.

Use of data protected by a contractual restriction may constitute breach of contract, and the dataset owner may have the right to bring a claim for damages or other legal remedies.

When considering conducting data scraping or data mining it is important to think about how you plan to or have gained access to the dataset you are proposing to work on: Were you asked to accept terms and conditions online? If the dataset is on a website is there a ‘terms and conditions’ link? Has access been negotiated in a way that required signature of a bespoke contract? Read the terms carefully and seek legal advice on anything that seems unreasonable.

Confidentiality restrictions

UK law provides for protection of information where: –

- It should have been obvious to a reasonable person that the information was confidential;

- An obligation was created in some way to keep the information confidential.

Where such information is then used or shared without permission and to the detriment of the rightsholder, there may be a claim for breach of confidentiality. There is a defence for breaches ‘in the public interest’. For example, if exclusive access has been granted to a party to collect or obtain data, another party collecting or using unofficial data in the same context may be in breach of confidentiality. A recent court case about race day information upheld confidentiality as the only way to stop a rival using the race day information – collected by unauthorised visits to the racecourse.

When thinking about conducting data scraping or data mining it would be relevant to consider whether the data or database is supposed to be confidential – or if your access to the data in the first place was only granted on the basis that the data would remain confidential. Is the data specialised or commercially sensitive?

Competition law

While contract law, copyright law and other special protections for information may inhibit data scraping and data mining, users may separately consider whether competition law enables access to data. Competition law tries to regulate and stop anti-competitive behaviour. Data producers and owners should consider whether regulating access to, withholding or preventing access to data could, in some circumstances, amount to an abuse of competition law.

Competition aims to control two forms of behaviour: –

- Entering into anti-competitive agreements; and

- Abuse of a dominant market position.

A dataset owner who is treating competitors differentially when it comes to data scraping or data mining, or who is withholding or preventing access to data in order to maintain or increase their own market position, may be at risk of breaching competition law. This is a specialist area and you should seek legal advice if you are concerned about the behaviour of a dataset owner.

Legal language

Ryanair Ltd v PR Aviation BV (C-30/14) EU:C:2015:10; [2015] 2 All E.R. (Comm) 455 (ECJ (2nd Chamber)) found ‘In the view of the court, the Directive must be interpreted as meaning that it is not applicable to a database which is not protected either by copyright or by the sui generis right under that Directive, so that arts 6(1) , 8 and 15 of that Directive do not preclude the author of such a database from laying down contractual limitations on its use by third parties.’

Please note that the CJEU decision mentioned above was made when the UK was still part of the EU and therefore bound by EU law. Following the end of the transition period (31 December 2020), the Supreme Court and Court of Appeal in the UK can decide to depart from pre-Brexit CJEU case law if they consider it ‘appropriate to do so’. However, until either of these senior courts decide to do so, the UK courts will continue to follow pre-Brexit CJEU judgements.

Shortly before Brexit, the UK High Court case of 77M Ltd v Ordnance Survey Ltd [2019] gave no indication that the UK senior courts intended not to follow pre-Brexit CJEU judgements. This case gave detailed consideration to a range of data scraping activities and applicable terms and conditions and to the UK exception that permitted some authorised extraction of data for ‘material open to public inspection or on an official register’. Interestingly, the judge observed ‘I have to say I am not convinced that the fact that a user wanted to operate for a profit must necessarily rule out the idea that they were doing acts for the purpose of disseminating information about matters of general scientific, technical, commercial or economic interest’ – but ultimately this was not a deciding factor in the case.

Legal references

The SGDR exceptions are specified in:

- Regulation 19, 20, 20A, Copyright and Rights in Databases Regulations 1997

- Schedule 1 to the Copyright and Rights in Databases Regulations 1997

The UK Copyright and Rights in Databases Regulations 1997 are available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1997/3032/contents

This regulatory space is evolving fast both nationally and internationally.

‘Data adequacy’ is an important concept under which data can flow freely between jurisdictions that offer similar levels of protection: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/ro/ip_21_3183

While the EU and UK provisions are currently treated as equivalent, post-Brexit the UK is also seeking new global data adequacy partnerships that are based on principles that depart from EU law: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-unveils-post-brexit-global-data-plans-to-boost-growth-increase-trade-and-improve-healthcare

The European Commission’s proposed EU Data Act is a new regulation to establish a harmonised framework for the access to and use of data generated in the EU across all economic sectors: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/data-act-proposal-regulation-harmonised-rules-fair-access-and-use-data.

Related

Algorithms

It is important for users to have a better understanding of how to deal with the influence of algorithms on the production, distribution and consumption of creative works, and the implications for copyright.

Research & Private Study

Students and researchers often need to make use of materials which are copyright protected. In the context of their research or study, they may have to make copies or use extracts of those materials.

Text & Data Mining

The electronic analysis of large amounts of copyright works allows researchers to discover patterns, trends and other useful information that cannot be detected through usual ‘human’ reading. This process, known as ‘text and data mining’…