16. The Pantages

When Mary sees Lord Vane at the entrance of the Pantages theatre, there is a paperboy distributing copies of the Evening Paper with the headline ‘The Suicide of the sculptor Harkin and tonight’s play at the Pantages’. This is a reference to Each In His Own Way, a work by the Italian playwright Luigi Pirandello (1867 – 1936). Each In His Own Way is a play about the production of a play based on ‘real’ events.

Producing creative works based on real facts and events raises interesting questions about the complex relationship between reality and artistic expression, and the role that copyright plays. This relationship is further complicated when a work draws upon copyright works made by another author. Some of these questions are explored and discussed within this Case File #16.

NON-COPYRIGHTABLE MATERIALS

As discussed in previous case files (see for example Case File #7), copyright does not protect an idea. In addition, copyright does not protect other materials like data, information, facts, and the details of historic events.

Even so, there may be situations in which an author takes these materials and reworks them into a creative work that attracts copyright protection. Consider the life of Henry VIII. The facts and events surrounding his life are not copyrightable, but the original way in which someone might turn them into a book or movie is copyrightable. Several examples of this exist: the television show The Tudors, the novel Wolf Hall by the award-winning author Hilary Mantel, and the National Geographic documentary ‘The Madness of Henry VIII.’ In each instance, the author enjoys copyright in their creative work, but the underlying information and facts remain available for anyone to use.

This is also briefly explored in Case File #18 in relation to the lawsuit about Dan Brown’s blockbuster thriller, The Da Vinci Code. It was alleged that Mr Brown had copied substantial material from an earlier book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail. Mr Brown disagreed, arguing that he simply copied information, facts and ideas from the other book. For details of how the case was resolved, see Case File #18.

INFLUENCE AND APPROPRIATION

Authors do not create their work in a vacuum. They often have similar ideas and are influenced by the ideas of others when creating new works. In itself, this is not a bad thing. Indeed, copying can be very creative, and creativity often involves copying. What is important is that the copying is lawful and does not infringe another author’s rights. Ideas, though, are not protected by copyright.

For example, imagine a movie in which a group of social outcasts travels the galaxy to fight evil and save the universe.

Do you have a one in mind? Is it Star Wars? Galaxy Quest? The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy? Guardians of the Galaxy? Each is based on a common premise or idea, but the films themselves are very different and benefit from each creator’s own personal expression. At the same time, the basic underlying science-fiction plot remains available for others to use to create new works, so long as the new work does not copy a substantial or whole part of one of the earlier films.

But what about when an author does want to make use of someone else’s work in creating something new? In doing so, the author might incorporate certain aspects of another work – or even the entire work – in her creation. This is often referred to as ‘appropriation’, or the use of pre-existing works, sometimes with little to no transformation. Appropriation involves ‘borrowing’ creations from other authors and including or assimilating them into new works.

Indeed, many authors consider themselves to be ‘appropriation artists,’ meaning they create new works which intentionally draw on the works of others. Doing so is considered key to the artists’ concept for making the work: they create new work by recontextualising the existing work. The works created by appropriation artists may well be eligible for copyright protection, however, some question whether appropriation art is sufficiently original to enjoy copyright protection at all.

FOR DISCUSSION: APPROPRIATE APPROPRIATION?

So, what happens when an author appropriates another author’s copyright work into a new creation? In some cases, things can get quite controversial as to where inspiration ends and plagiarism or copyright infringement begins (see for example Case File #18).

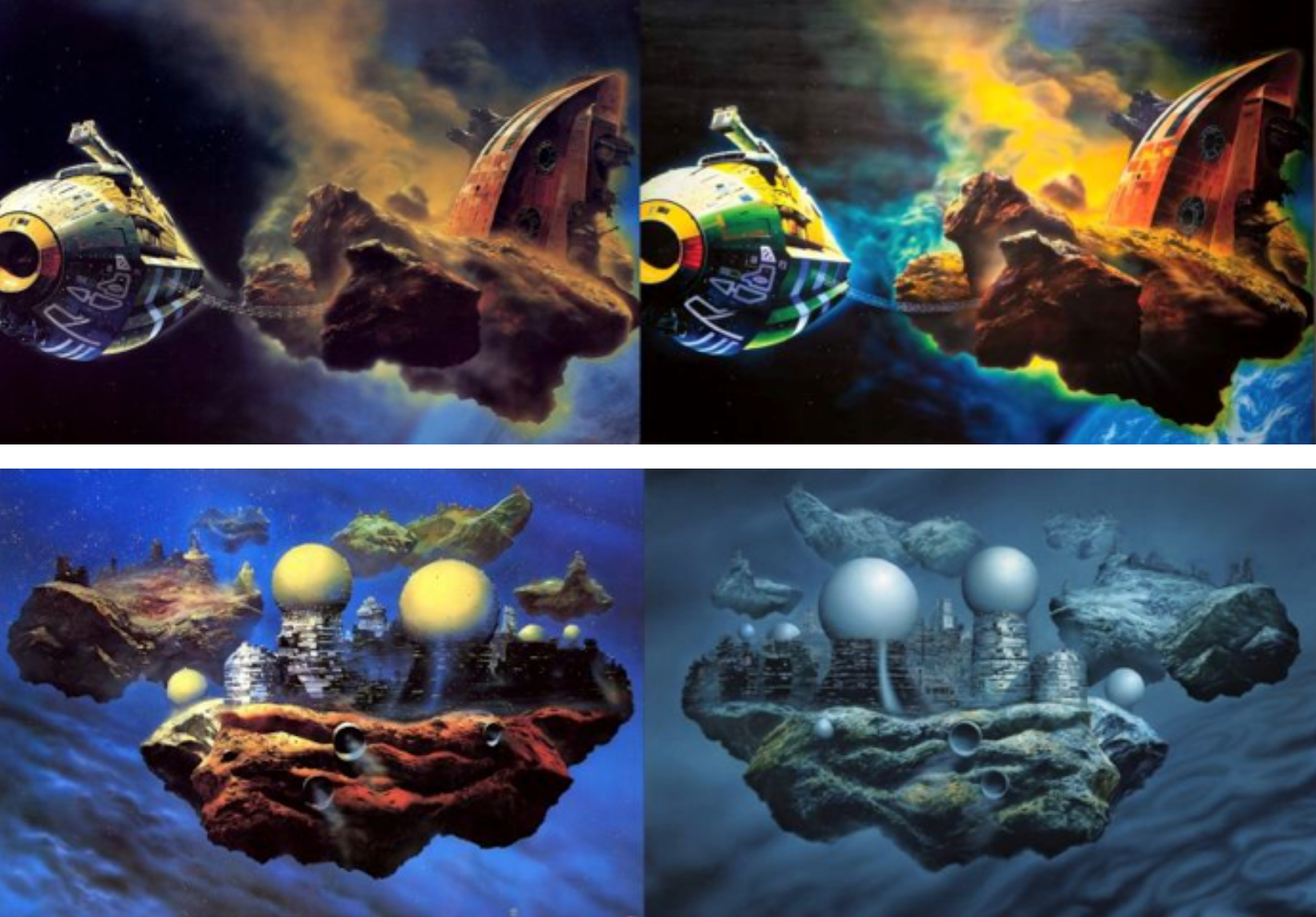

Tony Roberts’ Double Star and Glenn Brown’s The Loves of Shepherds, available at How to Understand Why an Awesome Book Cover Became Expensive Fine Art, by Charlie Jane Anders, http://io9.gizmodo.com/how-to-understand-why-an-awesome-book-cover-became-expe-1497969800

Consider the two images above. The image on the left is an illustration by Antony Roberts for the cover of Robert A. Heinlein’s novel Doublestar, published in 1974. The image on the right is a 2000 Turner Prize nominated work by Glenn Brown, titled ‘The Loves of Shepherds.’ In the Turner Prize catalogue, Brown’s entry made no reference to Robert’s illustration or Heinlein’s novel. At first glance, it might seem that the image on the right has simply ‘copied’ the other. Others might describe this as creative appropriation.

Indeed, appropriation is at the heart of Brown’s work. Brown meticulously recreates images ‘borrowed’ from art and popular culture by transforming the appropriated image, whether changing its colour, position, orientation, mood or size. Brown begins by importing the original image into an image editing programme like Photoshop and alters the image and its subject matter to form his desired composition. He then paints the image by painstakingly applying thin layers of paint to a canvas. The process produces a painting with a mirror-smooth surface which, in some cases, can take more than a year to create.

In order to receive copyright protection under UK law, literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works must be original and, in general, so long as the creation of the work involves some labour, skill, judgement or effort, the work will be considered to be original. However, when dealing with works that expressly copy from an existing work, satisfying the originality criterion may not be so straightforward. For example, in the case of Interlego AG v. Tyco Industries Inc (1989) Lord Oliver commented as follows: ‘copying per se, however much skill or labour may be devoted to the process, cannot make a work original’. He continued: ‘[A] well executed tracing is the result of much labour and skill but remains what it is, a tracing’. In relation to artistic works, he considered, the change in the work must be ‘visually significant’; there must be ‘some element of material alteration or embellishment’ to make the new work an original work.

Based on this premise, do you think Brown’s appropriation is ‘original’? To follow that, even if it is, do you think Brown’s appropriation infringes on Roberts’ copyright?

Brown has appropriated works from other science-fiction illustration artists, such as Chris Foss.

Chris Foss’ Stars Like Dust and Glenn Brown’s Ornamental Despair, available at How a Science Fiction Book Cover Became a $5.7 Million Painting, by Charlie Jane Anders, http://io9.gizmodo.com/how-a-science-fiction-book-cover-became-a-5-7-million-1497486808

Chris Foss’ Floating Cities and Glenn Brown’s Bocklin’s Tomb, available at How a Science Fiction Book Cover Became a $5.7 Million Painting, by Charlie Jane Anders, http://io9.gizmodo.com/how-a-science-fiction-book-cover-became-a-5-7-million-1497486808

Both images on the left are by Chris Foss. Both images on the right are by Glenn Brown. Foss originally gave Brown permission to remix his work, but later became upset when he saw the final result. Indeed, both Roberts and Foss have expressed frustration with Brown’s appropriations. Roberts feels, ‘None of this would have been possible without my painting.’ Foss has also questioned the fairness of Brown’s use of his imagery because, although Foss created the original image, ‘this man gets all this kudos from basically lovingly repainting it.’

Brown has appropriated works of other artists, like Salvador Dali and Rembrandt. His work and technique draws on a long history of appropriation by other artists, like Picasso and Warhol, stressing the importance of appropriation in his own work and in seeking to make the relationship with art history as obvious as possible. Brown defends his work, saying his versions never look like the originals due to the alteration in colour, the difference in scale, redrawing, and embellishments. Indeed, many would advise witnessing the paintings in person to fully appreciate the scale of Brown’s work.

What do you think?

USEFUL REFERENCES

For useful information on the creative re-use of public domain works, see: www.create.ac.uk.

For a resource to help you calculate whether a work is in the public domain in the UK or other EU Member States, see www.outofcopyright.eu.

For more information on Glenn Brown’s works see http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/a-real-scene-stealer-glenn-browns-second-hand-art-is-the-subject-of-a-tate-retrospective-1622648.html#gallery.

For more information on Chris Foss’ see http://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-5-7-million-magazine-illustration.

Download the PDF version of Case File #16 – The Pantages.

More Case Files

13. The Multiple Rights

Mary Westmacott is a freelance screenwriter; she writes scripts for films. Scripts are written works that contain the words of a film (or a play, television programme, video game, and so on)…

14. The Missing Manuscript

The missing manuscript is the original script written by Mary and commissioned by Money Tree Productions. The term ‘original’ has different meanings depending on the context.

15. The Dream Job

Mary accepts a commission to write ‘an original script’ for ‘a film about a missing boy,’ not just for the ‘intriguing premise’ but also because ‘for once the contract terms were great; a dream job that would pay the bills for many years’.

17. The Typewriter

The design of the typewriter that Mary uses to write her scripts was inspired by Jack Torrance’s typewriter in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Famously, Kubrick’s The Shining is a film adaptation of Stephen King’s novel with the same title.

18. The Purloined Letters

Before she was murdered, Mary Westmacott had become increasingly concerned for her safety and state of mind. In her letter to Holmes she describes how, one night…

19. The Fateful Eight Seconds

As Watson enters the room we see Sherlock reading a newspaper. On one page, the headline reads: ‘Eight Seconds of Sporting Genius!’ The choice of headline was intentional….

20. The Lawful Reader

The headline ‘News Just In! Reading the internet is the same as reading a book’ refers to a copyright case in which the courts were asked to consider whether simply reading material online might infringe copyright.

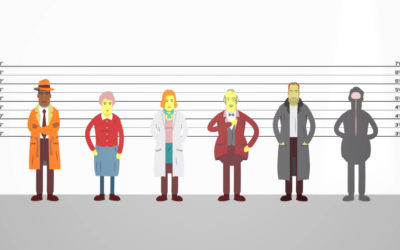

21. The Six Detectives

Mary’s problems began when she ‘started fleshing out the main character: the hero-detective’. Before settling on one and starting seeing the others everywhere, she considered six potential protagonists for her story.