3. SOUND RECORDING RIGHTS

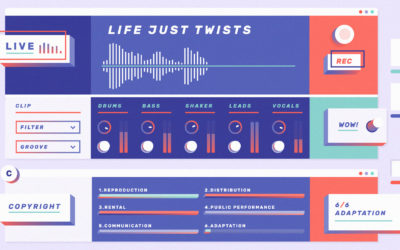

By recording their song Tina and Ben satisfy the ‘fixation’ requirement and their original song will be protected by copyright. But when they record their song they also create a new copyright work known as a ‘sound recording’, also sometimes known as a ‘master’. The copyright in a sound recording is different from the copyright in a song in a number of significant ways.

The ownership of the sound recording copyright rests with the ‘author’ of the recording. But this is not necessarily a human author in the usual sense of the word. In UK law the author of a sound recording is the ‘producer’, a legal term usually taken to be the record company that paid for the recording to be made.

So, if Tina and Ben make a recording of their song themselves, they will own the copyright in the recording. However, if they sign a deal with a record company, it is likely that the record company will be identified as the author and owner of the copyright in the sound recording (see Track 4).

The sound recording right also differs in duration from the copyright in the song. In the UK this copyright has a term of 70-years from release of the work. This is potentially a considerably shorter term than the copyright in the song of 70 years after the death of the last surviving author. Somewhat confusingly, this means the copyright in the sound recording may expire long before the copyright in the song featured on the recording. The duration of each copyright may vary depending on the country.

Alongside the sound recording copyright there are also related public performance rights. These can be split into: producers’ rights (usually those of the record company) and performers’ rights (those of the performers that feature on the recording).

Besides being the writers of the song, Tina and Ben also have performers’ rights in their recording. Performers routinely transfer most of these rights to a record company when they sign a recording contract. Although they may transfer control of these rights to the record company, by law they will retain some economic rights in their performances.

This means that when the sound recordings are broadcast or performed in a public place, a collecting society (see Track 6) will collect royalties and distribute them directly to producers and performers on shared basis.

You can find more information about ‘Copyright in sound recordings’ here: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/copyright-in-sound-recordings/copyright-in-sound-recordings

More Tracks

1. What constitutes a song?

A song is the combination of melody and words. Each is protected by copyright: the melody as a musical work and the lyrics as a literary work. One or the other could be used separately and still be protected.

2. Protecting your song

Copyright law protects against copying so the song must be ‘original’ and in some ‘fixed’ form (that could be copied). Tina and Ben could fix the song by recording it on a mobile phone or any other means of doing so, e.g. by writing it on a piece of paper.

4. Publishing and Recording Deals

Traditionally there are two main types of contracts or ‘deals’ musicians are likely to seek in order to reach a wider audience: a music publishing deal and a record deal.

5. Self-release: distributing music directly to the public

In the digital age many costs involved in recording and marketing music have been significantly reduced by the availability of affordable, accessible technologies.

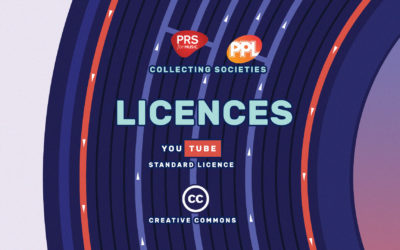

6. Public Performance, Royalties and Collecting Societies

To reduce transaction costs for rights holders and rights users alike, collecting societies have been established in order to collectively negotiate and issue blanket licences to users, and to collect and distribute royalties to rights holders.

7. Licences

Aside from lyrics and melody of the song, and the recording of the music, copyright also subsists in the script, the artwork, the voiceover and the film/video itself.