30. THE CREATIVE COPY

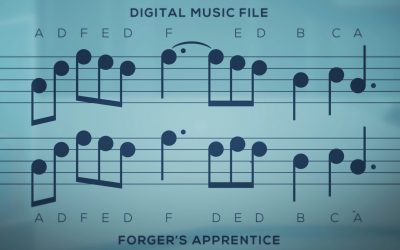

In The Missing Note, a digital file contains a recording of the soundtrack to the film The Forger’s Apprentice, but with one note missing. The missing note is the key to a cipher that holds the answer to the whereabouts of the anarchist group.

The melody in question is taken from the film score of The Godfather, written by the Italian composer Nino Rota, and it was subject of some controversy when the film was first released. In Case File #18 we considered the similarities and differences between plagiarism and copyright infringement. In this Case File #30, we consider the concept of self-plagiarism and how it relates to creativity and copyright.

COPYING AND CREATING

Many of the Case Files created for this resource explore when it is appropriate and lawful to borrow from and make use of the work of others. But, what about when creators borrow from themselves?

The author and playwright Luigi Pirandello is a good example of a creator who often reused and recycled his own earlier work. Indeed, in many respects, the practice of self-plagiarism lay at the heart of Pirandello’s writing and method.

For example, Pirandello’s novel, Her Husband [Suo Marito], first published in 1911, considers what it means to create original work, and what it means to be an author. The novel’s central character is Silvia Roncella, a writer who is unconcerned with the commercialisation of her work. Indeed, she often insists on giving her work away for free, which frustrates her husband’s attempts to benefit financially from her writing.

However, in the novel, the works that are attributed to Silvia are actually re-cycled re-presentations of some of Pirandello’s earlier texts. That is, Pirandello presents Silvia as the author of Pirandello’s own earlier work. The boundaries between quotation and original text are blurred in the novel in a way that encapsulates the extent to which Pirandello deliberately conflated copying and creation throughout his literary career. This was just one of the reasons that we wanted to borrow from Pirandello’s work when creating episode 2 of The Game is On! The Adventure of the Six Detectives.

Moreover, like Pirandello, and many others, we have also borrowed from our own earlier work in creating The Game is On! series. In this episode, for example, we reuse scenes and material from the first two episodes (can you spot them?). And, we’ll reuse material from this episode in the next two that follow (we don’t believe in spoilers, so you’ll have to wait and see).

AND THE OSCAR DOESN’T GO TO …

In 1972, Nino Rota’s score for the The Godfather, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, was nominated for an Oscar for Best Original Dramatic Score. However, the nomination was subsequently withdrawn by the Academy on the grounds that Rota – when writing the Love Theme for the film – had reused music from a score that he had written for the 1958 Italian film comedy Fortunella. The Academy argued that as Rota had reused his own music from an earlier film, the score to The Godfather could not be considered ‘original’.

With The Godfather out of the running, the Oscar for Best Dramatic Score that year was awarded to the film Limelight, written, produced and directed by Charlie Chaplin in 1952. Chaplin also co-authored the score with Raymond Rasch and Larry Russell. Although Limelight had first been released twenty years earlier, it had not been screened in Los Angeles until 1972; as such, it was eligible for nomination.

Whereas today the soundtrack to Limelight is not particularly well known, Rota’s Love Theme from The Godfather has become one of cinema’s most famous and recognisable pieces of music. And yet, Rota had indeed reused his tune from Fortunella, albeit played in a very different way. In Fortunella the tune is played as a fast march: it is upbeat, raucous, and full of energy. In The Godfather, the orchestration, tempo and mood are completely changed: the melodic line may be the same, but the effect – what the music evokes – is entirely different.

Rota’s act of self-plagiarism, whether conscious or unconscious, had other knock-on effects. Dino De Laurentiis, who produced Fortunella, subsequently reissued the Fortunella soundtrack featuring the ironic claim that it was ‘The Godmother of the Godfather’. De Laurentiis was seeking to capitalise on the scandal of plagiarism surrounding Rota’s Love Theme.

As it happens, two years later, Nino Rota and Carmine Coppola were awarded the Oscar for Best Dramatic Score for The Godfather II. Naturally, the film score for the Godfather II reused and recycled much of Rota’s original score for The Godfather.

CREATE, AND REPEAT

Artists often incorporate motifs and elements of their earlier work when creating new works. However, if they have sold the copyright in those earlier works to someone else, they run the risk of infringing copyright when creating their new work. For this reason the CDPA provides a specific exception allowing artists to reuse aspects of their earlier works. Section 64 states that where the author of an artistic work is not the copyright owner of that work, she does not infringe the copyright by copying the work in making another artistic work, provided she does not repeat or imitate the main design of the earlier work.

Consider, for example, an artist commissioned to paint a group portrait of seven or eight individuals. Later, the artist might reuse the sketches she made for the group painting to produce individual portraits. This type of use would fall within the scope of s.64: the artist would not infringe the copyright in the earlier painting as she is not repeating or imitating the main design of that earlier work.

Why do you think the CDPA specifically provides an exception for artists to reuse their earlier work, but not for authors or composers?

FOR DISCUSSION: TOO FAR? OR FAIR ENOUGH?

The melody at the heart of the mystery in The Missing Note is based on the Love Theme from The Godfather, by Nino Rota. Our version is an adaptation of Rota’s melody, by the Italian composers Pietro Bartolotti and Filippo Terni, under the supervision of Adriano Cirillo. Cirillo was taught by Nino Rota. The notes are the same, but the timing, phrasing and effect is different.

Main melody from the Love Theme, by Rota

Adaptation, by Bartolotti, Terni and Cirillo

But, have we infringed the copyright in the original melody? Or, does our reuse of the melody fall within one of the exceptions to copyright? Perhaps it qualifies as quotation (see Case File #25), criticism or review (see Case File #6), or even parody (see Case File #5)? Perhaps it falls within a different exception entirely? You can find more information about different types of copyright exception on the Exceptions page of copyrightuser.org. Is there another exception that might apply in this case?

USEFUL REFERENCES:

Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/contents

There are various websites that provide information and guidance about plagiarism and how to avoid it! Many of these websites have been developed by Universities seeking to educate their students about this increasingly important issue. One particularly helpful resource is ‘What Constitutes Plagiarism’ within the Harvard Guide to Using Sources: http://usingsources.fas.harvard.edu/what-constitutes-plagiarism

Other resources have been developed by commercial companies that specialise in developing tools and strategies to help students and educators understand and detect plagiarism within an educational context. For example, see: http://www.plagiarism.org/

Download the PDF version of Case File #5 – The Terrible Shark

Download the PDF version of Case File #6 – The Famous Pipe

Download the PDF version of Case File #18 – The Purloined Letters

Download the PDF version of Case File #25 – The Accidental Image

Download the PDF version of Case File #30 – The Creative Copy

More Case Files

28. The Musician and the Machine

In this Case File #28, we consider how copyright protects music and sound recordings – two different categories of copyright work.

29. The Double Score

In Case File #29 we explore the different kinds of permission one may need when making use of someone else’s music in a film or video.