28. THE MUSICIAN AND THE MACHINE

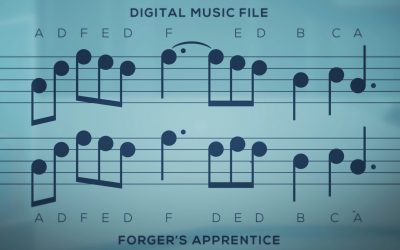

In The Missing Note, a digital file contains a recording of the soundtrack to the film The Forger’s Apprentice, but with one note missing. The missing note is the key to a cipher that holds the answer to the whereabouts of the anarchist group.

In Case File #23 we considered the different types of work that can be protected by copyright in the UK. In this Case File #28, we consider how copyright protects music and sound recordings – two different categories of copyright work.

WHAT IS MUSIC?

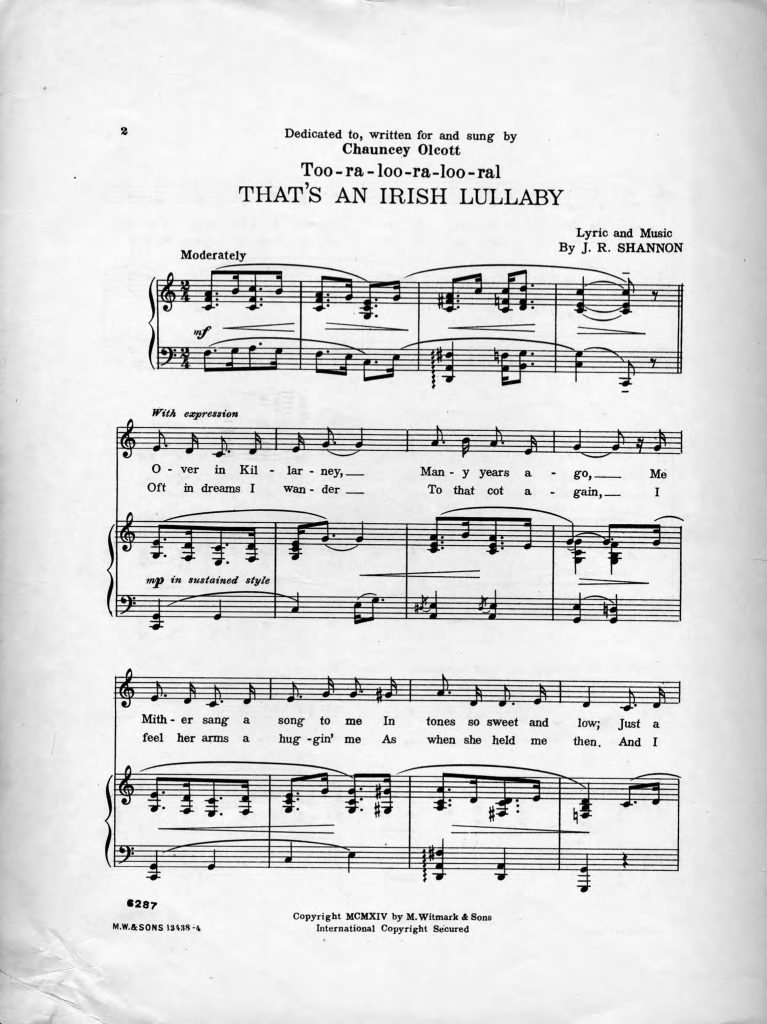

Music embodied in print form (that is, sheet music) has been protected by copyright since the late eighteenth century. Consider the sheet music for the song Too-ra-loo-ra-loo-ral, written in 1914 by the Irish-American composer James Royce Shannon (1881-1946). As Shannon died more than 70 years ago, the work is no longer in copyright. However, it provides a useful illustration of what would be protected as a musical work under the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 (the CDPA).

First, it is worth noting that, for copyright purposes, the lyrics accompanying the song are not a part of the musical work: the CDPA defines a musical work as ‘a work consisting of music, exclusive of any words or action intended to be sung, spoken or performed with the music’ (s.3(1)). Instead, the lyrics would be protected as a literary work, separate from the musical work. (In this case, however, both music and lyrics were written by Shannon.)

The notes on the score – the melody and the accompanying baseline and harmonies – are obviously part of the musical work. But, music is more than just notes on a page. Other elements that contribute to the sound of the music as it is performed can also be protected by copyright, such as the tempo (Moderately), instructions concerning the relationship between notes (such as musical phrasing or an arpeggiated chord), dynamics (mf or mp), or other directions for performance (With expression). Like stage directions accompanying a play, all of these various elements contribute to the musical work and as such may be protected by copyright.

WHAT IS A SOUND RECORDING?

Sound recordings were first protected in the UK under the Copyright Act 1911. Interestingly, at that time, they were protected as if they were musical works. Today, the situation is different: musical works and sound recordings are two different types of copyright work.

Under the CDPA a sound recording is defined as: ‘(a) a recording of sounds, from which the sounds may be reproduced, or (b) a recording of the whole or part of a literary, dramatic or musical work, from which the sounds reproducing the work or part may be produced, [and] regardless of the medium on which the recording is made or the method by which the sounds are reproduced or produced’ (s.5A(1)). This is a very broad definition. As a result, the Act provides protection for vinyl records, tapes, compact discs, digital audio tapes and any other media used to embody recordings.

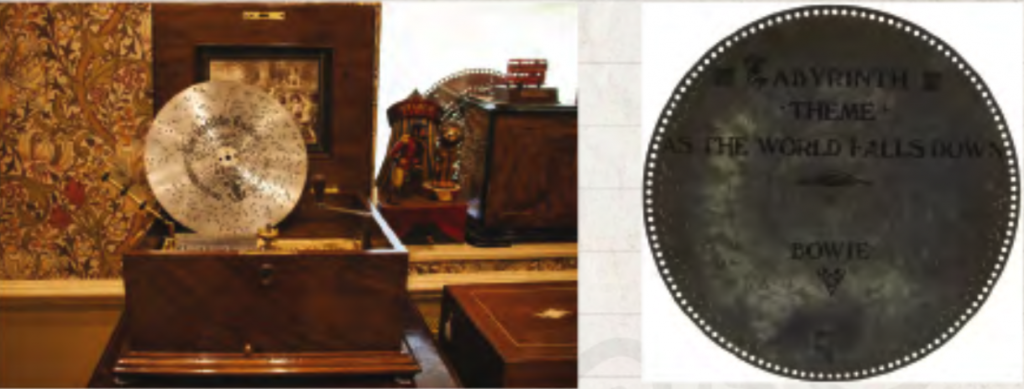

CURIOSITY: POLYPHON FANTASY

Labyrinth (1986) is an adventure fantasy film directed by Jim Henson and executive-produced by George Lucas. It stars the late David Bowie as Jarthe, the Goblin King. Bowie recorded five songs for the film, including As the World Falls Down which was also produced in a Polyphon format: that is, the music was cut onto a 19⅝-inch high-nickelled steel disc to be played on a mechanical music box. Only two copies were ever made: one to be used for the recording of the film score, and one for Bowie’s personal use.

The Polyphon steel disc format constitutes a sound recording for the purposes of the CDPA. The same would be true of a pin roll from a music box or a length of punched tape to be used in a barrel organ or a pianola.

Image left: A Polyphon 11-inch disc musical box, made in Leipzig (http://www.mechanicalmusic.co.uk/disc-players/)

Image right: David Bowie, As the World Falls Down, on a 19⅝-inch Polyphon disc

SONGS AND OTHER CO-AUTHORED MUSICAL WORKS: COPYRIGHT DURATION

Copyright in literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works expires 70 years from the end of the year in which the author died (s.12(2)). If a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is jointly authored, the 70-year term is calculated from the end of the year in which the longest surviving joint author died.

However, special rules about calculating duration of copyright in songs and other similar musical compositions were introduced in 2013. The CDPA was amended to say that when the author of a musical work and the author of a literary work collaborate to create works intended ‘to be used together’, the resulting works are treated as a ‘work of co-authorship.’ The concept of a work of co-authorship is similar to but distinct from the concept of a work of joint authorship. (You can read more about works of joint authorship in Case File #22.)

This change had an important impact on how duration is calculated for these types of work. Previously, duration of copyright in the music and the lyrics of a song would have been calculated independently of each other: that is, copyright in the music would come to an end 70 years following the death of the composer, whereas copyright in the lyrics would end 70 years after the death of the lyricist. Now, however, duration of copyright in a song that has been co-authored will last for 70 years from the end of the year in which the longest surviving co-author died.

This change has also resulted in work that was already in the public domain benefitting from a revived copyright.

Consider, for example, the songbook of George and Ira Gershwin. George composed music, and Ira was the lyricist. George died in 1937; Ira survived until 1983. In the UK, before the changes introduced in 2013, copyright in George’s music had expired on 31 December 2007. Now, copyright in George’s music has been revived and will expire 70 years from the end of the year in which Ira died: that is, on 31 December 2053.

SOUND RECORDINGS: COPYRIGHT DURATION

The rules on the copyright term in sound recordings have changed a number of times in recent years – in 1995, in 2001, and then again in 2013 – which can make calculating duration of protection more complicated than it should be. In general, though, copyright in a sound recording will last for 50 years from the end of the year in which the recording is made, or if published, played in public or communicated to the public during that period, 70 years after the end of the year in which the work is first published, played in public or communicated to the public (CDPA, s.13A(2)).

You can read more about the duration of protection in sound recordings here.

FOR DISCUSSION: WHEN NOT COPIED IS GOOD ENOUGH

Not every literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work will qualify for copyright protection. There is a minimum criterion set out in the CDPA which requires that all literary, dramatic, musical and artistic works should be original before they will be protected by copyright (s.1(1)). You can read more about the concept of originality in copyright law in Case File #14.

However, sound recordings do not need to be original; the CDPA only requires that a sound recording is not copied from a previous sound recording (s.5A(2)). This is a much easier criterion to satisfy than originality. Imagine, for example, a band has written a new song they want to record. In the studio they make various recordings, or ‘takes,’ each of which is essentially the same as the last. Even though each take is almost identical to every other take, they are all protected by copyright as individual sound recordings. None of them have been copied from a previous recording: each one is a new protected recording, even though they may not be original.

Why do you think the CDPA applies different criteria for protection to music and to sound recordings? Why must a musical work be original, whereas a non-original sound recording will be protected so long as it has not been copied from a previous sound recording?

USEFUL REFERENCES:

Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/contents

For further information on copyright duration in the UK, see Copyright Bite #1 – Copyright Duration: https://www.copyrightuser.org/copyright-bites/1-copyright-duration/

See also: Copyright and Digital Cultural Heritage: Duration of Copyright: https://copyrightcortex.org/copyright-101/chapter-6

The Sheet Music Consortium promotes access to and use of online sheet music collections by students, educators and the general public. Much of this material is in the public domain. Search for and download sheet music here: http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/sheetmusic/index.html

Download the PDF version of Case File #14 – The Missing Manuscript

Download the PDF version of Case File #22 – The Two Heads

Download the PDF version of Case File #23 – The Eight Categories

Download the PDF version of Case File #28 – The Musician and the Machine

More Case Files

29. The Double Score

In Case File #29 we explore the different kinds of permission one may need when making use of someone else’s music in a film or video.

30. The Creative Copy

In this Case File #30, we consider the concept of self-plagiarism and how it relates to creativity and copyright.