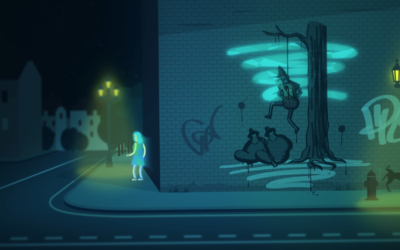

9. THE IMPROBABLE THREAT

In trying to persuade Holmes to take Joseph’s case, Watson asks: ‘What if it’s a threat? That’s what the graffiti might mean.’ These eleven words are based on dialogue from The Blind Banker, an episode of the BBC TV series Sherlock, in which Holmes, played by Benedict Cumberbatch, declares: ‘It’s a threat. That’s what the graffiti meant.’ That is, in writing our script for the video, we copied and slightly adapted nine words from the screenplay for The Blind Banker.

Like Case File #7 (The Matching Wallpaper), this Case File #9 concerns the concept of ‘substantial taking’. But whereas Case File #7 discussed substantial taking in the context of non-literal copying, in this Case File we explore what substantial or insubstantial copying means when borrowing literally from someone else’s work.

SUBSTANTIAL TAKING

Copyright infringement occurs when someone takes the whole, or a substantial part of, a copyright protected work without permission or the benefit of a copyright exception. So, taking an insubstantial part of a copyright work without permission is allowed. This is because the law recognises that no real injury is done to the copyright owner if only an insignificant part of the work is copied.

But what constitutes a substantial part? Substantial taking is considered by the courts to be a matter of quality, not quantity. So it is not just about how much you copy from someone else’s work, it is about the importance or value of the copied parts in relation to that work. This is because a small part of the original work may be highly significant to the piece as a whole.

For example, in one case the court decided that copying only a few lines from an unpublished version of Ulysses by James Joyce (1882 – 1941) was substantial because of the particular importance of those lines to the unpublished text. Another judge has commented that: ‘only a section of a picture may have been copied, or even only a phrase, from a poem or a book, or only a bar or two of a piece of music, may have been copied … In cases of that sort, the question whether the copying of the part constitutes an infringement depends on the qualitative importance of the part that has been copied, assessed in relation to the copyright work as a whole.’

This focus on the quality rather than the quantity of what has been copied can make it difficult to define precisely what amounts to a substantial copying.

THE CASE: Infopaq International A/S v Danske Dagblades Forening [2009] ECR I-6569

Infopaq International is a media monitoring and analysis company that provides its customers with summaries of selected articles from Danish daily newspapers and other periodicals. Articles are selected for summarising on the basis of search criteria agreed with Infopaq’s customers, and the selection is made by means of a ‘data capture process’. This process involved scanning articles to produce searchable text files, and then searching the text files to generate eleven-word snippets of text (the search word plus five words either side) which were both printed out and stored electronically. The text files were subsequently deleted.

One of the key questions to be answered in this case concerned whether the text extracts of eleven words amounted to unlawful copying from the original articles. Or, in other words, did copying just eleven words of text constitute substantial copying?

The Danish Supreme Court referred the issue to the Courts of Justice of the European Union. The judges decided that ‘an act occurring during a data capture process, which consists of storing an extract of a protected work comprising 11 words and printing out that extract, is such as to come within the concept of reproduction … if the elements thus reproduced are the expression of the intellectual creation of their author; it is for the national court to make this determination.’

That is, the Court of Justice considered that an extract of eleven words taken from a newspaper article could constitute a substantial part of that work, provided the extract conveys to the reader an element of the work which represents an expression of the intellectual creation of the author. In short, copying a sentence or even a part of a sentence from a literary work might be regarded as substantial copying.

When the case returned to the Danish Supreme Court Infopaq were found guilty of copyright infringement.

FOR DISCUSSION: QUALITY OR QUANTITY

What do you think about this case? Do you think that copying a short extract of just eleven words taken from a newspaper article should amount to substantial copying which might require the permission of the copyright owner? What if it was eleven words taken from an extremely long book or from a short poem? Or what if you are copying eleven words from a blog or a post on a social media platform such as Twitter?

When we copied nine words from the BBC screenplay for The Blind Banker did we engage in substantial or insubstantial copying? Does it matter that we slightly adapted the original text so that the statement from The Blind Banker became a question in our video? Or, if you copied our eleven word text without our permission would you be infringing our copyright?

USEFUL REFERENCES:

The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 is available here. Section 16(3)(a) provides that copyright in a work can be infringed by copying the work as a whole or any substantial part of it.

Designer Guild Limited v Russell Williams (Textiles) Limited (Trading As Washington Dc) [2000] UKHL 58 is available here.

Infopaq International A/S v Danske Dagblades Forening [2009] ECR I-6569 is available here.

Sweeney v MacMillan Publishers (2002) RPC 35 (the James Joyce case) is available here. You can also read a summary of the Sweeney decision here.

Download the PDF version of Case File #9 – The Improbable Threat.

More Case Files

1. The Red Bus

The Adventure of the Girl with the Light Blue Hair starts with a red double-decker bus travelling across Westminster Bridge, with the Houses of Parliament in the background.

2. The Monster

One of the graffiti that scare the toymaker Joseph portrays a monster eating his ‘beautiful, wonderful toy’. The image of the monster is inspired by two different artistic works

3. The Baker Street Building

Sherlock Holmes and John Watson discuss Joseph’s case at 221B Baker Street. The above illustration is inspired by two sources…

4. The Anonymous Artist

Joseph, the toymaker, has asked the police to identify the culprit making ‘dreadful images’ of his toy, portraying it in violent situations.

5. The Terrible Shark

This illustration from our video depicts a terrible shark-like creature about to eat Joseph’s toy. It was inspired by two different images…

6. The Famous Pipe

The pipe has been associated with the image of Sherlock Holmes since Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s (1859 – 1930) stories were first published in The Strand Magazine with illustrations by Sidney Paget (1860 – 1908).

7. The Matching Wallpaper

In the background of Holmes and Watson’s apartment you can see wallpaper with ‘flowers scattered over it in a somewhat impressionistic style’.

8. The Dreadful Images

The ‘dreadful images’ that scare Joseph, the toymaker, are graffiti drawn all over the ‘fictional land called London’. The illustration above, depicting Joseph’s toy hung from a tree, is based on an actual place in London.

10. The Uncertain Motivation

Joseph, Sherlock Holmes and the Girl with the Light Blue Hair are all creators: Joseph draws and designs toys; Sherlock composes music; and the mysterious girl is an accomplished street artist.

11. The Mutilated Work

In trying to persuade Holmes to take the case, Watson argues that: ‘If you were a professional musician, you wouldn’t want people copying or mutilating your work’.

12. The Hollywoodland Deal

Joseph explains to Holmes and Watson when and why the dreadful images of his beautiful, wonderful toy began to appear all over London. When ‘some guys’ from Hollywoodland approached him ‘to option a movie’…