THE LAWFUL READER

As Watson enters the room we see Sherlock reading a newspaper. On one page, the headline reads: ‘News Just In! Reading the internet is the same as reading a book.’ The choice of headline was intentional. It refers to a copyright case in which the courts were asked to consider whether simply reading material online might infringe copyright.

In this Case File #20 we consider the legality of browsing the internet and whether, from a copyright perspective, reading online is fundamentally different from reading a physical book, newspaper or magazine.

WHEN READING INVOLVES COPYING

Using the internet involves copying. Simply browsing a website involves the transmission of copies through internet routers and proxy servers to your computer or mobile device. When you view a webpage online, temporary copies of that page are made on your screen and also in the internet ‘cache’ on your hard drive. The use of an internet cache is a universal feature of browsing technology: it allows you to search and browse the internet efficiently and effectively. Indeed, without the use of a cache the internet would not function properly.

For this reason, reading online is technologically different from reading a book or a magazine. That is, whereas reading a physical book does not involve making copies of the text in that book, reading the same text online does involve copying. So, when you read or browse online are you infringing copyright? This was the question which the UK Supreme Court had to address in Public Relations Consultants Association v. The Newspaper Licensing Agency (2013).

THE CASE: Public Relations Consultants Association v. The Newspaper Licensing Agency (2013) UKSC 18

At the heart of this case was a very simple question: does reading material online involve making infringing copies? European and UK copyright law contains an exception that permits making temporary copies of protected works as long as the temporary copy: i) is transient or incidental; ii) is an integral part of a technological process intended to enable the lawful use of a work; and iii) has no independent economic significance.

The Newspaper Licensing Agency (the NLA) argued that this exception did not apply to browsing material online. One of their main arguments concerned copies that were made in the cache. Normally, material copied to the cache will remain there for two to three weeks before it is automatically deleted by the computer as a result of the continued use of the browser. However, the NLA pointed out that it is possible to adjust the settings on a computer to enlarge the cache and so extend the time it retains the copies while the browser is in use. Moreover, if a user simply closed down their computer or device, then copies in the cache might remain there indefinitely until the browser was used again. The NLA argued that in neither of these situations could cached material be regarded as temporary copying.

In the Supreme Court, Lord Sumption rejected these and other arguments put forward by the NLA. The purpose of the exception, he commented, was to enable the internet to function correctly and efficiently. That, in turn, required making temporary copies within the cache of an end user’s computer. Without caching material, the internet would not function properly. With that in mind, he continued, it would make no sense if the exception did not permit the ordinary technical processes associated with browsing (that is, making copies on screen and copies in the cache). In short: browsing is lawful.

It is important, however, to distinguish between simply reading material online and making a more permanent copy or record of that material. That is, while browsing is lawful, downloading or printing out material made available online will typically require the permission of the copyright owner (unless another copyright exception applies, for example, fair dealing for private study). The exception for temporary copies allows you to read online, but nothing more.

FOR DISCUSSION: READING IS READING IS READING

In delivering his opinion, Lord Sumption was keen to make the point that reading copyright material on the internet should be treated in the same way as reading a physical book, newspaper or magazine. That is, while technologically reading online might involve making temporary copies on the screen and in the cache, the law should not make any distinction between reading online and reading offline. He continued:

If it is an infringement merely to view copyright material, without downloading or printing out, then those who browse the internet are likely unintentionally to incur civil liability, at least in principle, by merely coming upon a web-page containing copyright material in the course of browsing. This seems an unacceptable result, which would make infringers of many millions of ordinary users of the internet …

However, what if the content you are reading online has been posted there unlawfully? That is, what if the copyright owner has not granted permission for their material to be made available online in the first place? Should the law draw a distinction between browsing lawful and unlawful content? If so, how would you know whether the material has been posted lawfully or unlawfully?

USEFUL REFERENCES

Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/contents

Public Relations Consultants Association Ltd v. The Newspaper Licensing Agency Ltd & Others [2013] UKSC 18, available here: www.bailii.org/uk/cases/UKSC/2013/18.html

Download the PDF version of Case File #20 – The Lawful Reader.

More Case Files

13. The Multiple Rights

Mary Westmacott is a freelance screenwriter; she writes scripts for films. Scripts are written works that contain the words of a film (or a play, television programme, video game, and so on)…

14. The Missing Manuscript

The missing manuscript is the original script written by Mary and commissioned by Money Tree Productions. The term ‘original’ has different meanings depending on the context.

15. The Dream Job

Mary accepts a commission to write ‘an original script’ for ‘a film about a missing boy,’ not just for the ‘intriguing premise’ but also because ‘for once the contract terms were great; a dream job that would pay the bills for many years’.

16. The Pantages

When Mary sees Lord Vane at the entrance of the Pantages theatre, there is a paperboy distributing copies of the Evening Paper with the headline ‘The Suicide of the sculptor Harkin and tonight’s play at the Pantages’…

17. The Typewriter

The design of the typewriter that Mary uses to write her scripts was inspired by Jack Torrance’s typewriter in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Famously, Kubrick’s The Shining is a film adaptation of Stephen King’s novel with the same title.

18. The Purloined Letters

Before she was murdered, Mary Westmacott had become increasingly concerned for her safety and state of mind. In her letter to Holmes she describes how, one night…

19. The Fateful Eight Seconds

As Watson enters the room we see Sherlock reading a newspaper. On one page, the headline reads: ‘Eight Seconds of Sporting Genius!’ The choice of headline was intentional….

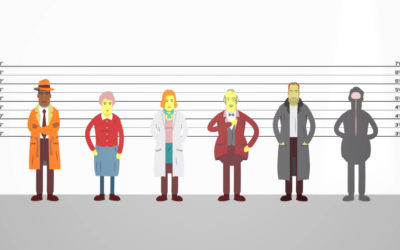

21. The Six Detectives

Mary’s problems began when she ‘started fleshing out the main character: the hero-detective’. Before settling on one and starting seeing the others everywhere, she considered six potential protagonists for her story.