24. THE RETRIEVED IMAGE

The Adventure of the Forger’s Apprentice references many films, such as Hail, Caesar! (US, Joel and Ethan Coen, 2016) and Pulp Fiction (US, Quentin Tarantino, 1994). Pulp Fiction is directed by a filmmaker who is known for his extensive film knowledge and for making numerous references to other films in his own work. Hail, Caesar! nostalgically points to a world that doesn’t exist anymore by referencing the golden era of Hollywood studio film production. These filmmakers have been able to play freely with their extensive knowledge of film history and to draw creative inspiration from the many films they have seen.

But where do films go after they are out of circulation? Can we still see them when we want to? Does anything need to happen to older film material to bring it back to the screen? No matter how films are produced – digitally, or photochemically as was the industry standard until quite recently – several steps need to be taken before you can enjoy most material on a screen again, whether that’s on a cinema screen or on your own laptop. But who is entitled to take those steps?

This Case File #24 considers film as cultural heritage, the preservation exception for archive material, as well as some of the wider implications of preservation and restoration.

PRESERVATION EXCEPTION FOR ARCHIVE MATERIAL

As we have seen in some of the previous Case Files (have a look at #5, #6 and #19), you are free to make use of a copyright work, without seeking the owner’s permission, if your use falls within one of the copyright exceptions. The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (the CDPA) sets out various exceptions, concerning non-commercial research and private study, quotation, news reporting, education, and other uses.

Recent changes in the law have made it easier for galleries, libraries, archives, and museums to make copies of creative works in their collections to preserve and make use of them for future generations (see sections 40A-43A of the CDPA). Here we will focus on just one of those exceptions: copying for preservation purposes (s.42).

Having a preservation exception that applies to films is particularly important. Film can be a very fragile material. Indeed, most films from before the 1950s were shot on highly flammable nitrate, which is no longer safe for use. Without an exception allowing copying for preservation purposes many of these historic films could not be copied in their entirety onto a more stable material for preservation, restoration and use.

Section 42 informs us that a librarian, archivist or curator of a library, archive or museum may, without infringing copyright, make a copy of an item in that institution’s permanent collection in order to preserve or replace that item in that collection (s.42(1)(a)), or to replace an item in the permanent collection of another library, archive or museum that has been lost, destroyed or damaged (s.42(1)(b)). Typically, the item that is being preserved or replaced must be held as part of the institution’s collection to enable researchers or members of the public to access and reference the work on the institution’s premises.

The condition that a film needs to be part of the collection kept wholly or mainly for the purposes of reference on the institution’s premises might prove to be a problem. For instance, academic researchers may consult films at the archive itself, but archive films are often screened at international film festivals, shown in local cinemas, or made available online so members of the public can enjoy and appreciate them. Does this mean these films are no longer kept mainly for reference on the institution’s premises, and so do not fall within the preservation exception? Perhaps yes, perhaps no: it could be argued either way.

The preservation exception also states that if it is ‘reasonably practicable’ to purchase a replacement copy of the work then you cannot make a preservation copy (s.42(3)). For archivists in general, and film archivists specifically, this condition will generally not prevent relying on the exception. The CDPA does not make it entirely clear what ‘not reasonably practicable to purchase a replacement’ means, but in the case of certain films, it is easy to understand how purchasing a replacement copy would be impossible. Consider silent cinema, roughly defined as films with no synchronised soundtrack and/or spoken dialogue, produced until the mid-1930s: estimated survival rates are less than 20% of worldwide production. Many of the surviving silent films are considered unique copies; that is, there are no known other copies of the same film in any of the world’s other film archives. In most cases, it will therefore not be possible to purchase another copy.

Of course, we should also note that many silent and other historic films will be out of copyright, so an archive would not have to rely on an exception or the former copyright owner’s permission for use. For a resource to help you calculate whether a work is in the public domain in various EU member states, see www.outofcopyright.eu

AN AMERICAN IN PARIS

Film preservation is usually only a first step in a larger restoration process. Passive preservation, for instance, can be as simple as improved storage conditions, whereas active preservation can entail the creation of duplicate copies. The ‘restoration’ of film can encompass anything from minimal interventions – such as image stabilisation to compensate for the film’s warping and shrinking over time – to interventions including the reconstruction of the film’s story, and digital image restoration in which the film’s images are individually retouched.

An interesting example that shows the complexity of some of these restoration processes is a recent French discovery. The negative of the 1916 film Sherlock Holmes (US, Arthur Berthelet), starring the American stage actor William Gillette as the title character, was (re)discovered in the vaults of the French national film archive, the Cinémathèque française. The film was found after having been thought lost for nearly 100 years. (It seems obvious that it would be difficult to purchase a replacement.)

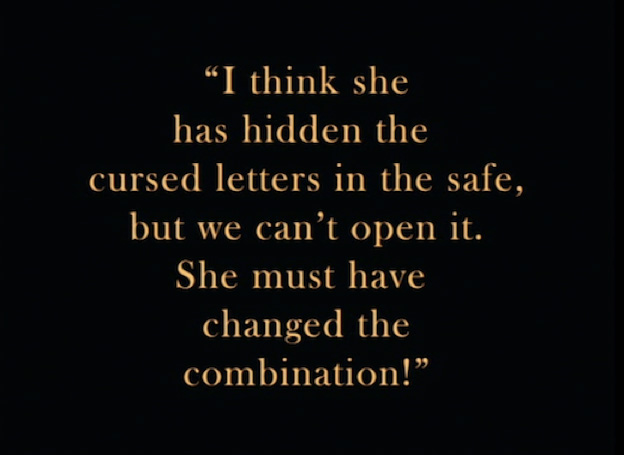

American production company Essanay shipped the film negative from the US to France in 1919. Three years after the film had its initial run in the US, and with Europe freshly out of WW1, Essanay saw new opportunities for exploiting its material abroad. The film was cut into 4 chapters for the French market, as serial films were popular in Europe at the time, and the intertitles in English were translated into French. (Before the invention of sound, intertitles – images of text that are inserted in the film – helped explain the story of the film or dialogue between the characters, and in the case of foreign productions these were translated to appeal to a local audience.) The negative was then printed at a French laboratory, observing colouring instructions as indicated on the film rolls. But after it had played in local cinemas for a while – the film was distributed in weekly chapters – the copies disappeared from public view. It is unclear how the negative material ended up and resurfaced in the Cinémathèque’s vaults all these years later.

The San Francisco Silent Film Festival (SFSFF) restored the film in collaboration with the Cinémathèque française. In bringing the film back to the big screen, the SFSFF commissioned one of the leading film restoration laboratories L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna, Italy, to scan the film’s individual images, so that subsequent digital image restoration – such as dust and scratch removal – could be carried out. It also translated the film’s French intertitles back into English, in consultation with William Gillette’s original manuscripts, which are preserved at the Chicago History Museum.

One of the intertitles in the film, which in the restoration process was translated from French back into English

In this case, the SFSFF did not have to ask anyone for permission to undertake the restoration process. In the US, the film is out of copyright: it is in the public domain, as the film had a theatrical release date from before 1923. (Indeed, in the US, any work with an authorised publication date from before 1923 is automatically in the public domain.) The fact that the film is in the public domain in the US, however, does not mean that the film is also in the public domain in the United Kingdom (or, France). Read Case File #22 and #23 to see how duration of copyright protection is calculated in relation to film in the UK.

THE MISSING LINK

Preservation and restoration processes can have far-reaching cultural implications. In the case of Sherlock Holmes, some of them seem obvious. Sherlock Holmes fans as well as William Gillette fans were elated with the news that the long lost film had been found and was going to be restored.

Being able to see the first man who personified Sherlock Holmes, in not only his sole surviving performance as Holmes but also in the only film he ever made, fills in a missing link in the understanding of the character. Gillette had been playing Holmes on stage for a few decades before he took on the role on film. Indeed, the film is a reproduction of Gillette’s four-act play of the same title, so the film also sheds light on the actor’s play of Holmes. Gillette’s portrayal of Holmes is generally understood to be the basis of the modern image of the detective.

FOR DISCUSSION: FOR PROFIT OR POSTERITY?

Do you think that the preservation exception is a helpful tool in the daily work of archives?

The Adventure of the Forger’s Apprentice also references such film classics as The Great Escape (US, John Sturges, 1963) and 8 1/2 (IT, Federico Fellini, 1963). Both films have recently been digitally restored for their 50th anniversary. The Great Escape, for example, was restored for a large sum of money by its rights holder MGM.

The film material of Sherlock Holmes was found in the French national film archive, which is an institution that is ‘not-for-profit’. Do you think that it would have made a difference if the film material had been found elsewhere – in a ‘for-profit’ institution, for instance? Do you think there is a relationship between copyright ownership and restoration projects? Are copyright owners more likely to spend money and time in preserving and restoring historic films than national libraries and archives?

USEFUL REFERENCES:

The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 is available here: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/48/contents

Sections 40A-43A set out the exceptions concerning the use of work within certain institutional contexts, such as libraries, archives, and museums.

You can find lots of information about exceptions for libraries, archives and museums in Chapter 8 of ‘Copyright 101’ of Copyright Cortex, available here: https://copyrightcortex.org/copyright-101/chapter-8

For more information about film restoration, see Mark-Paul Meyer and Paul Read (Eds.), Restauration of Motion Picture Film (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2000).

Download the PDF version of Case File #22 – The Two Heads

Download the PDF version of Case File #23 – The Eight Categories

Download the PDF version of Case File #24 – The Retrieved Image

More Case Files

22. The Two Heads

In this Case File #22 we consider the concepts of joint authorship and joint ownership of a copyright work.

23. The Eight Categories

In this Case File #23 The Eight Categories we consider the different categories of work that can be protected by copyright in the UK.

25. The Accidental Image

In this Case File #25 we explore the relationship between documentary filmmaking, the re-use of other people’s work and copyright exceptions.

26. The Recorded Performance

In this Case File #26 we look at the protection conferred to actors and other performers by performers’ rights.

27. The Interview Tape

In this Case File #27 we look at the different types of rights that may be ‘caught’ in the recording of interviews.