12. THE HOLLYWOODLAND DEAL

Joseph explains to Holmes and Watson when and why the dreadful images of his beautiful, wonderful toy began to appear all over London. When ‘some guys’ from Hollywoodland approached him ‘to option a movie’ featuring his toy, Joseph decided to go along with the deal: after all, ‘they offered lots of money’. But as soon as word got out about the deal, that’s when the graffiti started.

This Case File #12 considers who owns the copyright in a work when it is first created, as well as different ways in which the copyright in a work can be commercially exploited, whether by assignment or by licence.

FIRST OWNERSHIP OF COPYRIGHT

The Copyright Designs and Patents Acts 1988 sets out that the author of a work is also the first owner of the copyright in that work. There is, however, one major exception to this basic rule: if you are employed by someone else, and you create work during the course of your employment, the copyright in that work will generally belong to your employer.

Joseph is self-employed. As such he is the first owner of the copyright in the original drawings for his beautiful, wonderful toy. As the copyright owner, Joseph enjoys a bundle of exclusive economic rights such as the right to copy his work, the right to issue copies of his work to the public and the right to communicate the work to the public, for example, by posting it online. This means that Joseph can prevent others from doing any of these things without his permission, unless their use is otherwise permitted by law.

When he is approached by the businessmen from Hollywoodland about making use of his toy in their movie, Joseph has a choice: he can assign the rights in his work to them, or he can grant them a licence to make use of his work.

ASSIGNMENTS

An assignment of copyright involves a transfer of the ownership of the copyright from one person to another.

However there is no need to assign the entire bundle of economic rights in a work at the same time to the same person. Indeed, assignments of copyright can be quite specific about what rights are being transferred (what you are allowed to do), for how long (a year, or ten years, or perhaps for the entire copyright term), and jurisdiction (where in the world you can make use of the work). For example, an author might assign the right to turn her work into a film to an American production company, while assigning the right to publish the work to a British-based publisher. The publisher, in turn, might assign the right to publish the work in a foreign language, whether in Europe, Asia or South America, to an overseas publisher.

Whatever the nature of the assignment, it is important to know that the assignment must be in writing and signed by or on behalf of the assignor (that is, the person making the assignment).

LICENCES

A licence is essentially a permission to make use of a work in a way that, without permission, would constitute copyright infringement. In other words, the grant of a licence means the licensee (the person to whom the licence is granted) can make use of the work without infringing the copyright in the work.

When granting a licence the copyright owner retains an interest in the copyright; that is, unlike an assignment, with a licence no property interest passes from the copyright owner to the licensee.

As with assignments, licences can be quite specific in terms of the rights involved, and the duration and geographic reach of the permissions granted. You can read more about licensing and exploiting copyright works on the Copyright User website.

People often get the two different spellings of licence/license confused. To clarify:

- Licence (spelt with a ‘c’) is the noun: ‘I grant you a licence to make use of my work’.

- License (spelt with an ‘s’) is the verb: ‘I license the use of my work to you’.

THE CASE: Noah v Shuba [1991] FSR 14

Dr Noah was a specialist medical practitioner who worked as a consultant in the Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre of the Public Health Laboratory Service (the PHLS). While he was working for the PHLS he wrote a medical pamphlet, A Guide to Hygienic Skin Piercing.

The PHLS claimed that, as Dr Noah’s employer, it owned the copyright in the pamphlet. PHLS pointed to a number of factors in support of its claim: Dr Noah had discussed the content of the pamphlet with his colleagues in work; he made use of the PHLS library in preparing his manuscript; he asked his secretary to type up the manuscript; and, the PHLS had agreed with Dr Noah to cover the costs of printing and publishing the Guide. For all these reasons, PHLS claimed copyright in the work.

Dr Noah disagreed. Although he was PHLS’s employee, he argued that the work had not been written in the course of his employment.

The judge agreed with Dr Noah. Of particular importance, in the judge’s view, was that Dr Noah had actually written his manuscript at home in the evenings and at the weekends, and that he had done so on his own initiative and not at the request or on the direction of his employers.

FOR DISCUSSION: WHOSE IS WHAT?

When considering copyright ownership disputes between employers and employees the courts often consider whether making the work falls within the normal type of activity that an employer could reasonably expect from or demand of the employee. That certainly seemed to be a relevant consideration for the judge in this case. Do you think the judge came to the correct decision?

Do you think the law strikes the right balance between the interests of employers and employees in presuming that employers typically own the copyright in work created by their employees? Can you think of any professions in which the presumption should be that employees retain the copyright in their work?

What would your advice be for Joseph? Should he assign rights to the Hollywoodland film-makers, or grant them a licence?

USEFUL REFERENCES:

Noah v Shuba [1991] FSR 14

The Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 is available here. Section 11 sets out the basic rules on the first ownership of copyright. Also, sections 90-92 for relevant provisions on assignments and licences.

You can find lots of information about copyright licensing and managing your rights on various UK collecting society websites, such as Authors Licensing and Collecting Society, PRS for Music, DACS, and others.

Download the PDF version of Case File #12 – The Hollywoodland Deal.

More Case Files

1. The Red Bus

The Adventure of the Girl with the Light Blue Hair starts with a red double-decker bus travelling across Westminster Bridge, with the Houses of Parliament in the background.

2. The Monster

One of the graffiti that scare the toymaker Joseph portrays a monster eating his ‘beautiful, wonderful toy’. The image of the monster is inspired by two different artistic works

3. The Baker Street Building

Sherlock Holmes and John Watson discuss Joseph’s case at 221B Baker Street. The above illustration is inspired by two sources…

4. The Anonymous Artist

Joseph, the toymaker, has asked the police to identify the culprit making ‘dreadful images’ of his toy, portraying it in violent situations.

5. The Terrible Shark

This illustration from our video depicts a terrible shark-like creature about to eat Joseph’s toy. It was inspired by two different images…

6. The Famous Pipe

The pipe has been associated with the image of Sherlock Holmes since Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s (1859 – 1930) stories were first published in The Strand Magazine with illustrations by Sidney Paget (1860 – 1908).

7. The Matching Wallpaper

In the background of Holmes and Watson’s apartment you can see wallpaper with ‘flowers scattered over it in a somewhat impressionistic style’.

8. The Dreadful Images

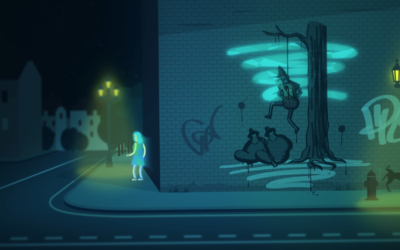

The ‘dreadful images’ that scare Joseph, the toymaker, are graffiti drawn all over the ‘fictional land called London’. The illustration above, depicting Joseph’s toy hung from a tree, is based on an actual place in London.

9. The Improbable Threat

In trying to persuade Holmes to take Joseph’s case, Watson asks: ‘What if it’s a threat? That’s what the graffiti might mean.’ These eleven words are based on dialogue from The Blind Banker…

10. The Uncertain Motivation

Joseph, Sherlock Holmes and the Girl with the Light Blue Hair are all creators: Joseph draws and designs toys; Sherlock composes music; and the mysterious girl is an accomplished street artist.

11. The Mutilated Work

In trying to persuade Holmes to take the case, Watson argues that: ‘If you were a professional musician, you wouldn’t want people copying or mutilating your work’.